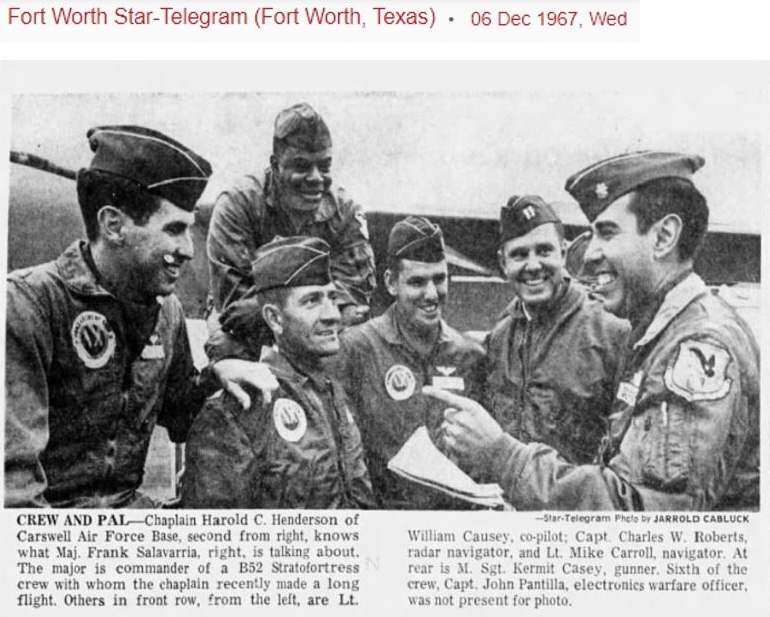

“I was Acting Wing Safety Officer at the time, and I got the call after midnight to come out to the command post at Carswell Air Force Base where the B-52 was stationed,” said Earl McGill, recalling the early morning hours of February 29, 1968.

McGill is a U.S. Air Force veteran pilot who flew B-29 bombers on 28 missions during the Korean War. He later flew B-47 jet bombers in the Cold War, and commanded a B-52 bomber during the Vietnam War as well. McGill published a book about his experiences as an aviator called “Jet Age Man.” The book includes a chapter about Meal-88, the B-52 that disappeared off Matagorda Island in the Gulf of Mexico in February 1968.

The chapter details McGill’s experience as part of the team from Carswell Air Force Base that investigated the loss of the eight-engine Strategic Air Command bomber.

“The colonel who was running the investigation told us not to speculate at all,” McGill recalled. “He said, ‘I don’t want to hear any speculation,’ and he was right to say that.”

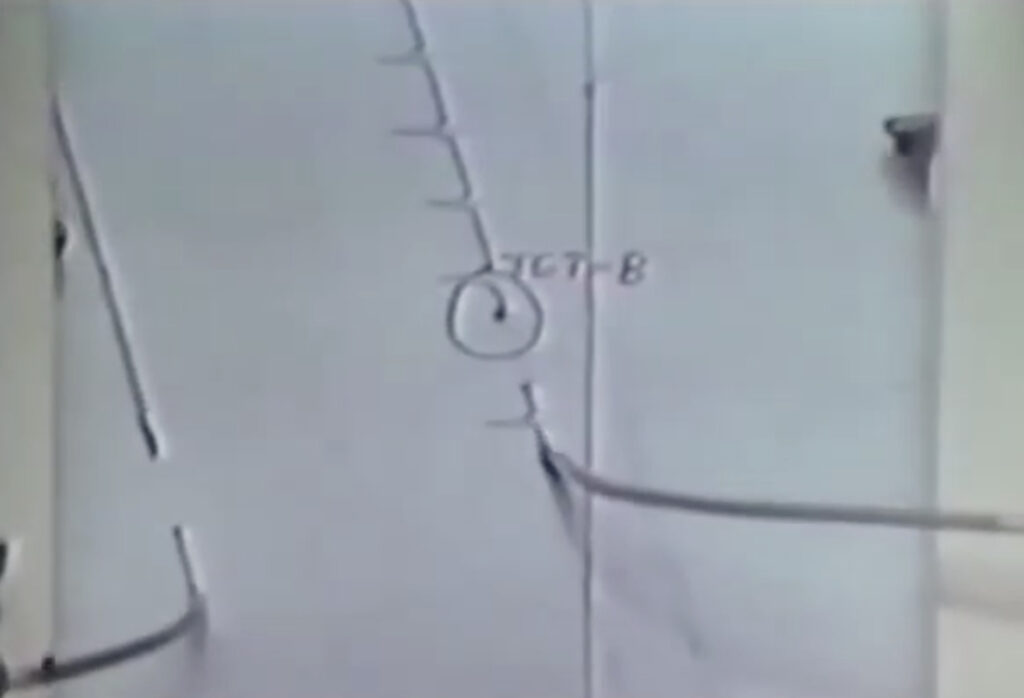

Being part of the investigation team meant spending 10 days at Matagorda Island, listening to audio recordings of radio transmissions between the crew on the plane and the people on the ground, and examining paper records from the night the plane disappeared. In 1968, Matagorda Island was home to a Radar Bomb Scoring (RBS) site, where airborne B-52 crews were put through their paces electronically, via simulated bombing runs at various altitudes.

“We all felt that this was really something extremely unlikely that happened,” McGill explained, still wondering decades later what might have caused Meal-88 to crash. “We didn’t lose that many B-52s, so most of the ones that were lost [were lost because of] extreme turbulence, a couple by mid-air collisions, and stuff like that.”

Bottom line, B-52 bombers don’t just vanish, McGill says.

Apart from the tapes and standard documents related to the RBS exercises, there wasn’t much to for McGill and the other Air Force personnel to investigate at Matagorda Island in the days immediately following the crash.

“The boats were out there looking for it the whole time we were there, and they had some pretty good high tech stuff,” McGill said. “But they never found it.”

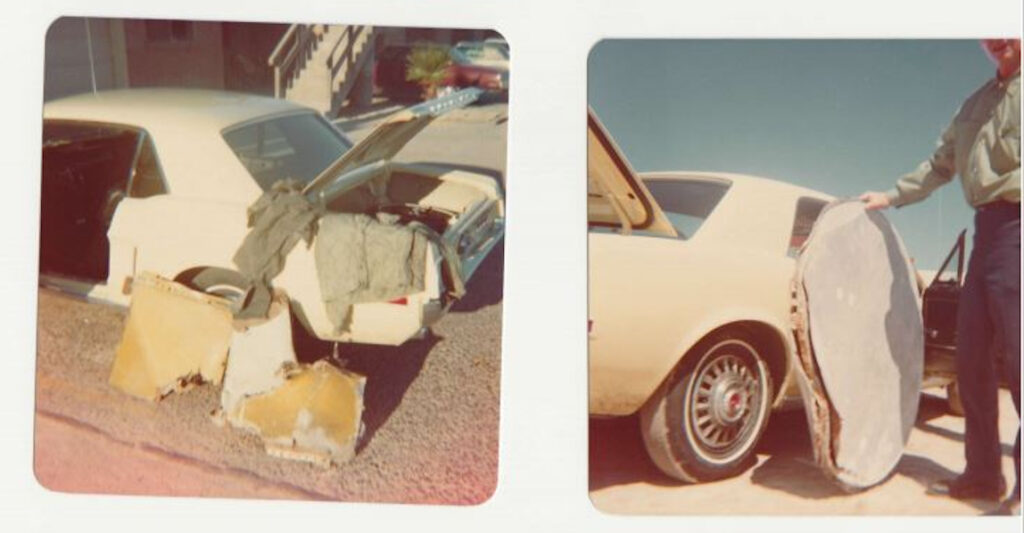

While U.S. Air Force searchers – with assistance from the U.S. Coast Guard – were unable to locate anything from the plane, on March 8, 1968, a school teacher found debris on a Texas beach. Almost immediately, officials at the Boeing facility in Wichita, Kansas confirmed for the Air Force that the object was from a B-52, it not necessarily specifically from Meal-88.

That’s when 23-year-old Cindy Dillaplain and her father decided to mount their own search for the B-52.

Cindy’s husband John Pantilla was a member of the crew. She was distraught over his disappearance, and by what she felt was an inadequate search, and hasty move by the Air Force to declare John and the other members of the crew deceased.

“The best way I can describe it, you feel like you have one arm and one leg and just half a body,” Cindy said about losing the love of her life. “So when you walk or you step or you go someplace, you’re just actually half a person, that other half of you doesn’t even show up.”

Cindy and her dad chartered a small plane and flew from Love Field in Dallas to Corpus Christi, Texas. From there, they flew over gulf waters near shore, but saw nothing of interest. However, on a scouring of the beach by foot and vehicle the next day, the two found several pieces of wreckage believed to be from the B-52 as well as a U.S. Air Force garment and an aviation air mask.

Hurrying home to Fort Worth on a Sunday afternoon, Cindy paused long enough to telephone Barbara Salavarria and tell her about the debris, and that they were transporting everything back to Cindy’s house. Barbara’s husband, Major Frank Salavarria, was the commander of Meal-88, and Cindy and Barbara were friends because their husbands were part of the same B-52 crew.

But, when Cindy and her dad reached Cindy’s home, someone was there waiting for them.

“In my yard in Fort Worth is two trucks – the Air Force Police – and they have guns,” Cindy said. “And they get out of their trucks and demanded possession of Air Force property.”

Cindy says the men confiscated the debris, and she never saw any of it again. She believes her phone and Barbara Salavarria’s phone were tapped, which she says is the only way the Air Force would have known that Cindy and her father were bringing their discoveries back to Fort Worth.

After a year waiting for John to return, Cindy moved on with her life and eventually remarried. But, as the years passed, she still wondered about what had happened to the B-52 and to her first husband.

In the early 1980s, she requested copies of pertinent documents from the Air Force, but it was only because of Cliff Sjolund tracking her down a few years ago that Cindy really began revisiting those long-ago events – events which understandably left a bad taste in her mouth when it comes to the Air Force.

“Cliff has been a godsend, and he has dedicated his life to the Air Force, and he tolerates my negative talk,” Cindy said. “And, bless his heart, I apologize every time I talk to him because of my negative outlook. I don’t know why he puts up with it, but he does. And he has a goal to right it.”

The goals of Cliff’s group that mean righting the wrong – preparing a detailed study of what might have happened, to find the B-52 and bring home the remains of the crew – were given an incalculable boost by what Cindy had taken time to do before she and her father headed back to Fort Worth from Corpus Christi on that Sunday back in March 1968.

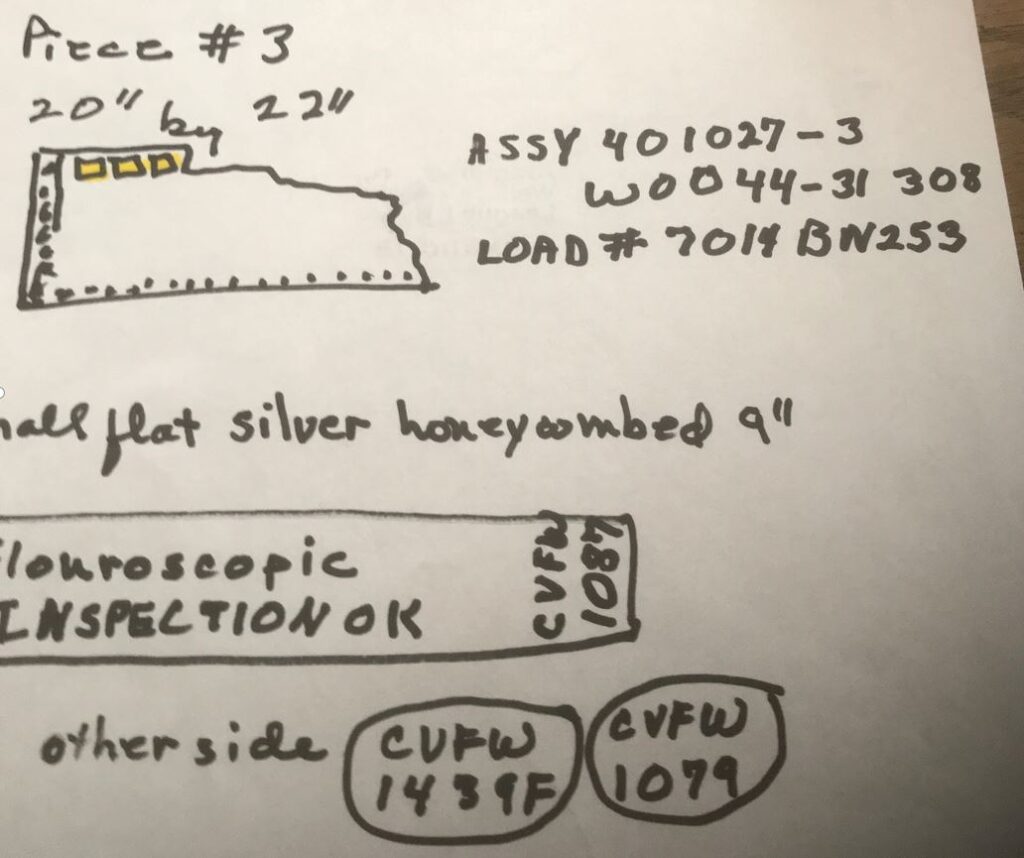

When Cliff found her a few years ago, Cindy still had the photos, sketches, measurements and detailed notes about the debris that she and her father had collected on the Texas beach.

To contribute to the effort to search for MEAL-88, please visit the project website: B52BomberDown.org.