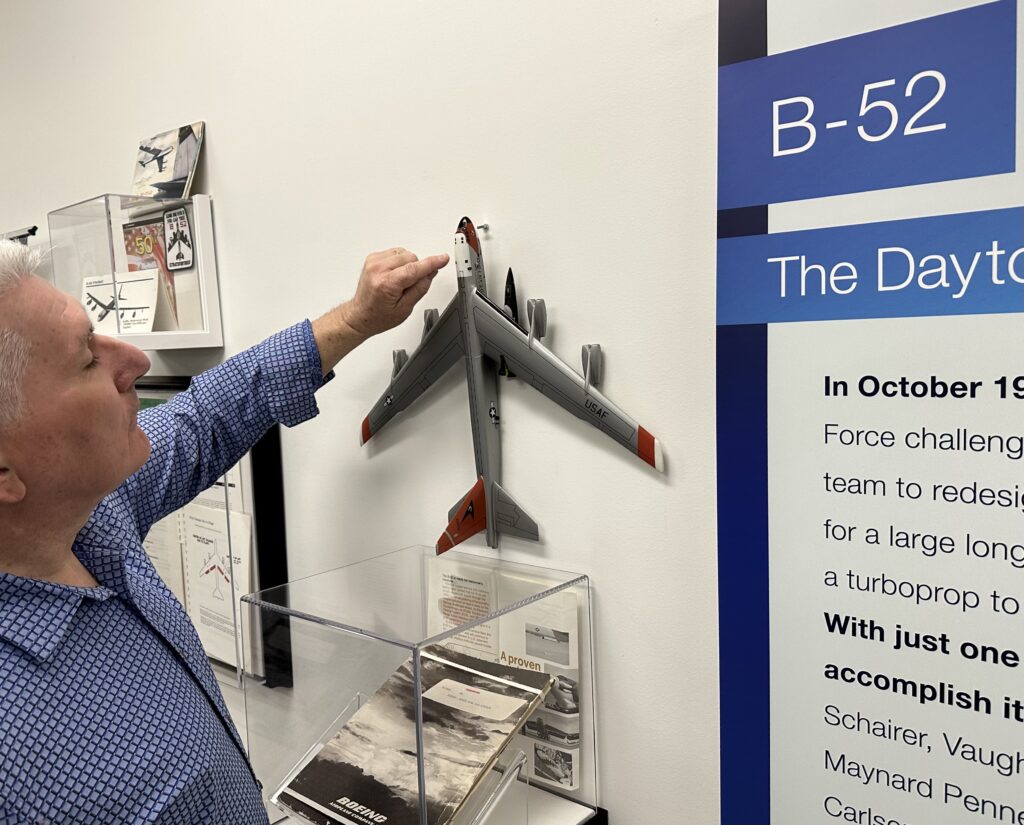

Dave Wellman is nearly 90 years old. He’s a docent at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and has been volunteering in this capacity for 31 years.

“I have experience in the Air Force and working for Boeing, and so I love and I live airplanes down here,” Wellman explained, one sunny afternoon in late winter. “I enjoy talking about anything airplane and history involved, especially the B-52, because the B-52 I flew in Vietnam on a number of missions.”

As Wellman describes his love of all things aviation and airplane related, he’s standing in the shadow cast by a huge wing. The wing is attached to a vintage B-52, which is on display outside the Museum of Flight. The giant bomber is there in that spot, in part, because of the efforts of Dave Wellman.

“This airplane we have here at the museum, we got this in about 1992,” Wellman explained. “They flew it in up to Paine Field in Everett, and it sat up there, and it just deteriorated badly.”

Paine Field is north of Seattle, and it’s where the Museum of Flight’s main restoration facility is located.

“A group of us Vietnam veterans, we got together, got with the museum, and we decided now is the time to bring that down here, to a thing we called Welcome Home Park,” Wellman continued. Part of Wellman’s motivation was to right a wrong: the way vets returning from a long and unpopular war in Southeast Asia were treated when they arrived stateside.

“It’s a park here to honor people that served in Vietnam, because when they returned home, a lot of folks, lot of the young men and people that served in there, they were not welcomed well in the 70s,” Wellman said. “And so now this is a chance to welcome people home.”

Like Cliff Sjolund, Jr., the man leading the quest to find MEAL-88, and like the men aboard that B-52 when it disappeared in 1968, Dave Wellman also flew B-52 bombers during the Cold War.

He went on “Alert” – those seven-day stretches of eating, sleeping and spending time with the other crew members and other crews near their parked bombers, 24 hours a day. The men were ready to respond in case the horn went off, which meant having to get their B-52s and deadly weapons airborne as quickly as possible. As commander, Wellman also led his crew through Radar Bomb Scoring (or “RBS”) training exercises, just like what the men aboard MEAL-88 were doing the night they vanished.

“BUF” (or “BUFF”)

As a B-52 commander, Dave Wellman also knows that the in-house and informal nickname for the giant eight-engine bomber – what he and all the other crew members called it – was “BUFF.”

That word is an acronym, Wellman explained.

“Its nickname is the ‘Big Ugly Fellow,'” he said. “‘B-U-F’ [which is] sometimes modified to a certain extent.”

Wellman’s family-friendly, museum-docent version leaves out one “F” – that’s the modification he referred to in his polite way. The second “F” happens to be the first letter in the gerund form of an expletive, in this case used as an adjectival modifier for “Fellow.” This ultimately adds a fourth character to the acronym and converts the nickname from “B-U-F” to “B-U-F-F.”

“It’s not very pretty,” Wellman said, clearly admiring the aircraft but sounding a little sheepish. “But it’s majestic.”

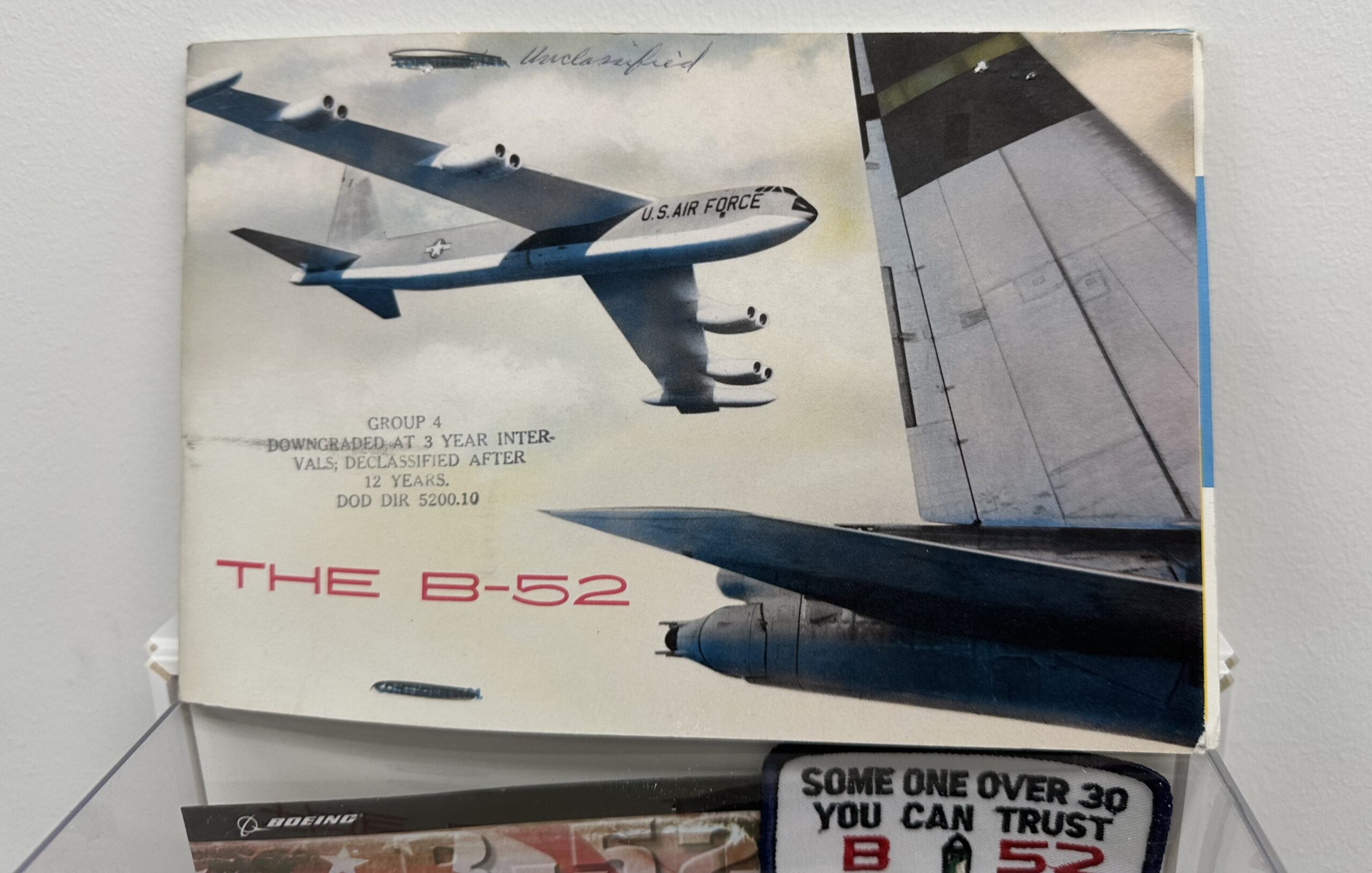

The B-52 on display at the Museum of Flight is across the street from Boeing Field, and is just down the road from where the first B-52 prototypes were built, and where the first model rolled out of the Boeing factory in 1952. The bomber has a long and remarkable history, with more than 70 still in service and flying missions for the U.S. Air Force nearly eight decades after the iconic aircraft was first designed.

Enduring Cold War Aviation Icon

“It is the icon of the Cold War, really,” said Mike Lombardi, Senior Corporate Historian for The Boeing Company. “And you can use terms like venerable, legendary . . . and it just goes along with its legendary status that it would have this incredible origin story.”

Lombardi oversees the Boeing Archives, located south of Seattle. He’s written books and given public programs about Boeing history, and, in particular, about the company’s iconic bombers of World War II, the Cold War and beyond – the B-17 Flying Fortress, the B-29 Superfortress, the B-47 Stratojet and, of course, the B-52 Stratofortress.

In response to a request from the U.S. Air Force for a long-range, high-capacity bomber, Boeing proposed a turbo-prop powered design and gave a presentation outlining their thinking at a meeting at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio in 1948.

There was only one problem, says Boeing’s Mike Lombardi: the Air Force didn’t want a turbo-prop bomber. They wanted a jet.

“It was a Thursday afternoon,” Lombardi explained. “The colonel that’s doing this evaluation says, ‘Come back Monday with a better idea.’”

The Boeing team – the “Boeing Brain Trust,” Lombardi calls it, including legendary aerospace engineering figures Ed Wells and George Shire – accepted the colonel’s challenge.

“So basically, over the weekend, they huddle in their hotel room there in Dayton, the Van Cleve Hotel,” Lombardi explained. “They pull the dresser over and then clear it off and get out their drafting pencils, and they start working this out.”

There were no 3-D printers in 1948, of course, but there was balsa wood, an easy to cut and easy to sculpt material long a favorite of modelers and other hobbyists, and readily available everywhere

“George Shire went down to the hobby shop downtown, bought some balsa wood and a hobby knife, and he sets out to start carving a model,” Lombardi continued. “And Ed Wells leads the team to develop a proposal. So they get on the phone, and they call back to Seattle, and they say, ‘Fire up the wind tunnel’ and they go through some calculations.”

“Gentlemen, this is the B-52”

“They draw up a jet bomber, and it’s going to need eight engines, it’s so big,” Lombardi said, “So they work it all out. Shire makes this model and puts it on a pedestal.”

On Monday morning, Lombardi says, comes the moment of truth.

“They go back to the colonel’s office . . . and they put the balsa wood model on his desk, and they give him this proposal, 33 pages is all it is,” Lombardi continued. “And they say, ‘Here’s our new idea based on your feedback.'”

“He looks at the model and opens up and looks at their proposal,” Lombardi said. “And he says, ‘I like this. Gentlemen, this is the B-52.'”

The Pilot’s Son

“I wonder sometimes, if I had my dad to raise me after age 10, would I have been a different husband and father?” Steve Salavarria asked. “Would my career have gone farther?”

Steve’s father knew the B-52 well. He was pilot of MEAL-88 the night it disappeared over the Gulf of Mexico. Steve – who was just a kid – was awakened early the next morning just after his mother opened the front door and got the news about the missing plane from Air Force officials.

“The doorbell rings, I didn’t hear that,” Salavarria explained. “What I woke up to was the wails of crying . . . my mother wailing. Not crying, but wailing.”

Steve’s mother was Barbara Salavarria, the first relative of a crew member tracked down by Cliff Sjolund decades ago. Barbara passed away a few years ago. Her son Steve says he thinks about the concept of closure, for the loss and grief from having a father who simply went to work one day and then never came back.

“I’ve talked with my sister and brother about it, and I’m not sure that we have ever thought that we lacked closure,” Salavarria said. “And so I’ve been thinking about it, you know, do I need closure?”

“I mean, if we find the the wreck and we get a dogtag out of it or something, is that going to give me closure?” Salavarria wondered. “I don’t know, because, see, that’s the thing. They didn’t have any counseling or psychology for us back in ’68 and ’69, so I don’t know.”

Should the search later this year for MEAL-88 succeed – should the B-52 be located, and perhaps identifiable remains of the members of the crew recovered – Steve Salavarria and the other family members of the missing men might finally be able to answer tough questions like these for themselves.

To contribute to the effort to search for MEAL-88, please visit the project website: B52BomberDown.org.