Eric Robinson loved to hike. He found happiness in the mountains. Over the course of his life, Eric trekked some of the world’s most stunning trails.

Eric had extensive experience in the outdoors, from his home range in the Grampians of Victoria, Australia (also known by the aboriginal name Gariwerd); to the High Sierra of California, United States; to the Himalaya of Nepal. Nothing pleased Eric more than a long walk in the mountains.

A meticulous planner, he always carried the essentials. He hauled everything he needed to survive a mishap or find his way if lost. So when Eric Robinson disappeared while on a solo hike in 2011, it shocked the people who knew him best. If anyone can survive in the wilderness, it’s Eric, friends and family thought. They believed he would emerge in his own good time, with a story to tell about the reason for the delay.

Hours stretched into days, then days became weeks. Searchers did not find any sign of Eric.

The Uinta Triangle

I first learned of the search for Eric as it was unfolding. It caught my attention for a few different reasons. I was working as a radio news reporter at the time, and I’d covered many other missing hiker stories. Eric’s seemed different, because of his extensive experience and detailed preparation.

More importantly, I knew a bit about the trail Eric was traveling when he disappeared. It traversed a wilderness area, far from roads or assistance in the case of any emergency. It’s an area I’d come to think of as the Uinta Triangle, a place where most people come and go without trouble, but where some vanish without explanation.

Most missing persons cases resolve quickly. Eric Robinson’s did not. Months became years and still, no answers emerged about his whereabouts. I continued to follow the case. Over time, I came to know Eric’s wife, Marilyn Koolstra, who shared the personal details of her experience searching for her husband in a land far from home.

Uinta Triangle is the story of the search for Eric. It’s an adventure journal, an investigation, a memoir and a love story.

“It’s a story of a missing person, but it’s also a legacy to that person for the love of what they did,” Marilyn said.

Who is Eric Robinson?

Before getting into the specifics of Eric’s disappearance, it’s important to understand a bit about the man himself and what motivated his wanderlust.

Eric Robinson was English by birth, Scottish by upbringing and Australian by choice. His parents, Victor Robinson and Margaret Walkingshaw, met during World War II, when they were both stationed at Stromness in the Orkney Islands. They married on July 1, 1944, just weeks after D-Day.

After the war, Victor and Margaret Robinson moved to a cottage near Victor’s home town of Ross-on-Wye in England. There, on March 19, 1947, the young couple welcomed their first and only child, a boy who they named Eric Joseph Robinson.

A little over a year later, Eric’s father Victor died unexpectedly in a motorcycle accident. A September 9, 1948 newspaper article stated Victor, along with his father and brother, were walking home from a movie after dark when the motorcyclist came around a bend and collided with Victor.

An inquest faulted Victor, 25, for being on the wrong side of the road when hit by the motorcycle. He never regained consciousness and died two days later.

Article from Sep 9, 1948 The Citizen (Gloucester, Gloucestershire, England)

Shortly after Victor’s death, Eric’s mother Margaret moved away from Ross-on-Wye and cut herself of Victor Robinson’s family. She raised their son in her hometown of Glencraig, Scotland.

“[Eric’s maternal] grandfather owned a few of the houses and he would go with his grandfather to collect the rent,” Marilyn said. “It was not a very wealthy existence.”

Eric’s mother Margaret did not tell him what’d happened to his father as he grew, and she soon remarried to a man named William Copeland.

“And it was not a happy one,” Marilyn said. “It was alcoholism and family violence.”

Eric Robinson moves to Australia

William Copeland, like many of the residents of Glencraig and surrounding areas, made a living in the coal mining industry. Economic shifts in the 1950s led to a collapse of that industry in Scotland. Copeland responded by packing his little family up and moving them to Australia in search of work.

“They emigrated as what we call in Australia Ten Pound Poms,” Marilyn said.

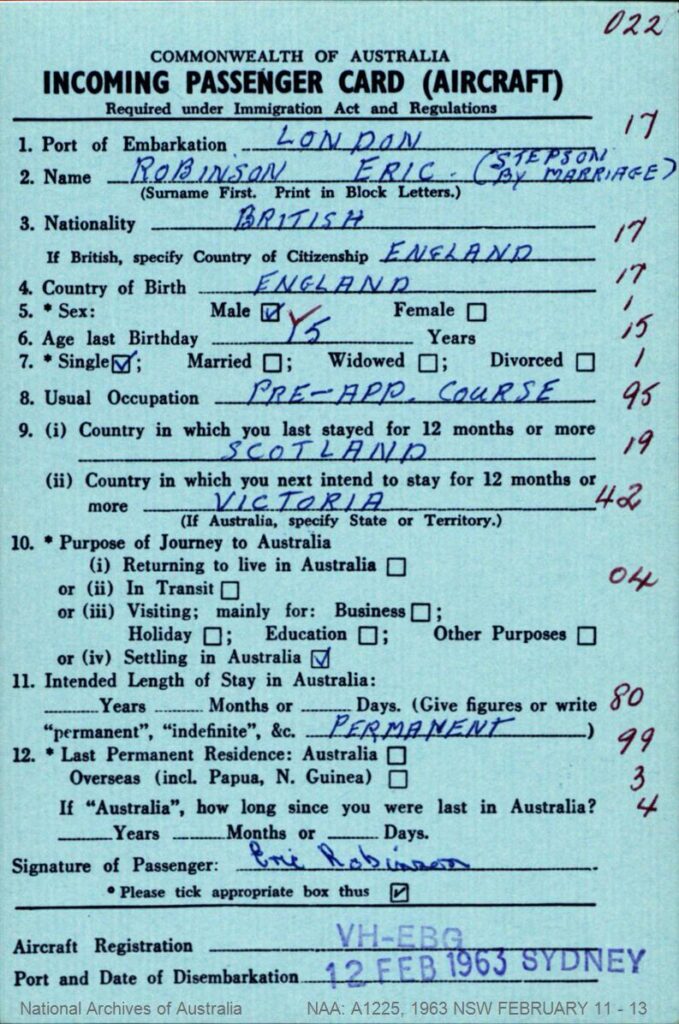

Emigration records show William Copeland, Margaret Walkingshaw Copeland and her teenage son, Eric Robinson, arrived in Sydney in February, 1963. They soon relocated to Melbourne, where Eric’s step-father enrolled him in an internship with the firm Ingersoll Rand.

William Copeland walked out on Margaret and Eric soon after settling in Melbourne. Lean years followed for Margaret and Eric, as they scraped out a difficult existence on the verge of poverty.

“[Eric’s] mum set up a dry cleaning business,” Marilyn said. “Eric saw firsthand the difficulties that some women experience in relationships.”

Even in the face of those difficulties, Eric found time to explore his new Australian home.

“His first car was a little Volkswagen Beetle, and he put the surfboard on the car and slept down the Surf Coast each weekend and back again,” Marilyn said. “He was a mad keen surfer.”

Eric Robinson’s first wife

Eric met a young woman at a rock-and-roll dance on the outskirts of Melbourne in 1966. Her name was Helen Petiach. She was a year older than Eric, but the two quickly bonded over their common experience as immigrants.

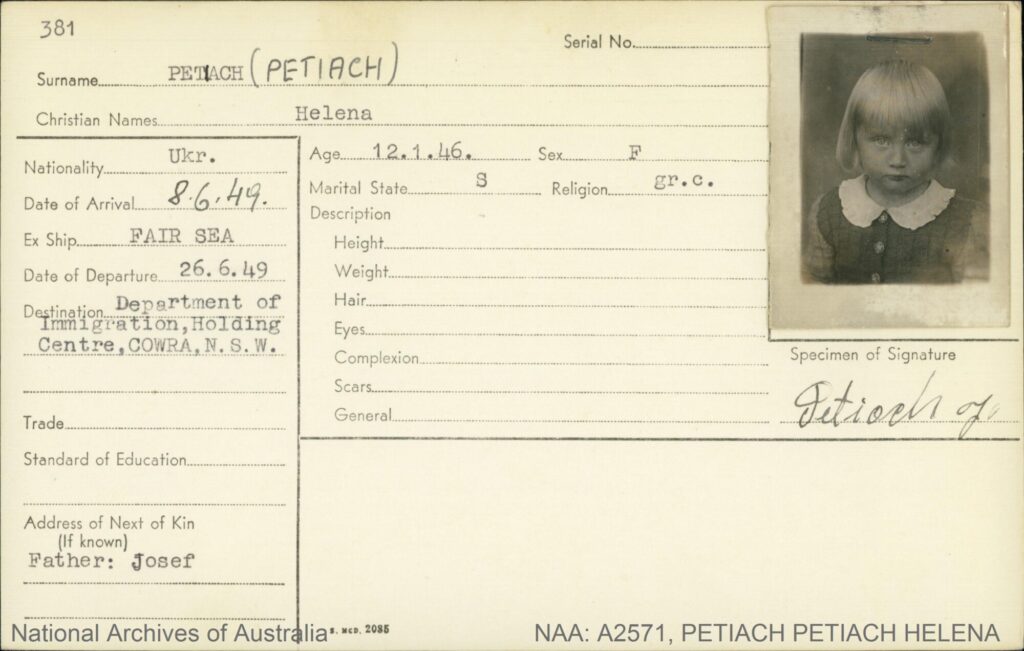

Helen was born in a displaced persons camp Salzburg, Austria, in January of 1946, just months after the end of World War II. Her parents, Josef and Maria Petiach, were Ukrainian Catholics who’d been forcibly removed from their homes on the Polish frontier by the Nazis during the war. Some records suggest Josef Petiach may have even been interred in the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Josef, Maria and young Helen Petiach arrived in Australia as refugees in 1949.

By the time Eric Robinson met Helen Petiach, she’d become a naturalized Australian citizen. Eric and Helen shared an identity as immigrants, which helped bond them together. But the circumstances of their respective upbringings were wildly different, which caused some conflict.

“His relationship with Helen was pretty volatile,” recalled Eric’s good friend, Russ Incoll.

Their courtship progressed to the point Eric proposed marriage, and the couple set a wedding date of August 30, 1969. But Eric soon had second thoughts.

“Eric decided that he didn’t think it was the right thing to do, to get married, and Helen said, ‘Look, if you leave me, I’ll kill myself,’” Russ said. “And then they got married.”

Eric was deferential to his bride. Although he was neither Catholic, or even all that religious, their wedding took place at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul cathedral in Melbourne. His deference only served to alienate his mother, Margaret.

So too did Eric and Helen’s decision to move to the suburb of Forest Hill. Margaret found herself living alone, far from her son. She decided to leave Australia and return to Scotland. Eric did not realize he would never see his mother alive again.

The death of Margaret Walkingshaw

Eric went to work for a company called DynaVac in February of 1970, as a “fitter and turner,” or mechanical engineer. The job provided him a solid income for the first time in his life, and also gave birth to many of his lifelong friendships.

On holiday weekends, Eric and his wife Helen would join coworkers on off-roading adventures all across eastern Australia. They camped and went bushwalking, or hiking.

“They had trips across Australia, through the Simpson and the Tanami Desert, up into Central Australia,” Marilyn Koolstra said.

In 1973, Eric gained Australian citizenship. He and his wife, Helen, were both fully integrated into their adopted country.

The young couple scraped enough money together for their first overseas vacation in 1974. They planned to visit Eric’s mother, Margaret, in Scotland. But Margaret died unexpectedly from stomach cancer that January, before Eric and Helen departed Australia. Margaret was just 51 years old.

Eric, by age 26, had lost the father he never knew, a stepfather he hated, and the mother he loved.

The birth of Eric Robinson’s new family

Eric’s wife Helen was diabetic. Doctors told the young couple it was unlikely they’d be able to conceive, due to Helen’s illness. But they beat the odds and in May of 1978, they welcomed a baby boy whom they named Glenn Craig.

Eric, Helen and little Glenn continued to explore the bush and backcountry of Australia.

Eric felt an ever-deepening connection to the land. He began joining protests against logging of old-growth forests, and in favor of protecting wild places.

Meanwhile, Helen’s health was deteriorating. Her kidneys were compromised and she required daily peritoneal dialysis. Still, she continued venturing out with Eric and Glenn.

That came to an end in May of 1990, when Helen caught infection that turned septic and killed her in a matter of hours. Eric suddenly found himself as a single father to a 12-year-old son, a role he struggled to fill.

In the wake of Helen’s death, Eric’s close friends took him out into the bush as a form of wilderness therapy. He hiked the Overland Track in Tasmania with two close work colleagues, John and Jeanette Sidwell.

“That probably was the first walk that got him back into it, got him going again,” John Sidwell said. “He loved his bush, and he loved hiking and getting out into the bush and wasn’t afraid to be out on his own.”

Eric sought solace in the outdoors from the three great wounds of his life: the early deaths of his father, his mother, and his first wife. From that point on, he held one ambition.

“His mantra was, ‘I’m going to do as many walks as I can, for as long as I can carry a backpack, because there’s more walks than I can achieve in a lifetime out there,'” Marilyn said.

A new romance blooms

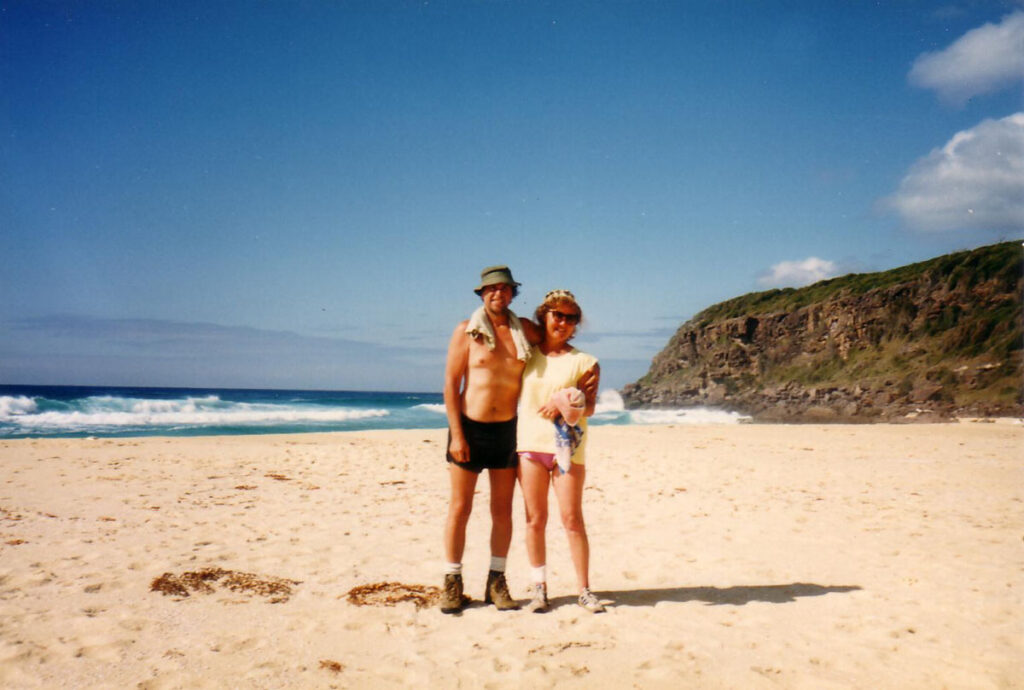

Eric met Marilyn Koolstra through an introduction agency, or dating service, a few years later. During their first date, Marilyn told Eric she enjoyed hiking.

“He was rapt that I loved walking,” Marilyn said. “We would always go somewhere at weekends. It was that love of walking, I think, that really drew us into a lot of activities together.”

Their courtship spanned more than a decade, during which they traveled and trekked together all across Victoria, and in New Zealand. A few years after marrying in 2005, Eric and Marilyn spent a month hiking the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal.

But Marilyn wasn’t always available, or willing, to hike with Eric. That was especially true as Eric’s ambitions in the outdoors grew. So he increasingly went out solo.

“We also talked about the safety angle of that,” Marilyn said. “I was saying, ‘Well, so far you’ve walked by yourself. Maybe you can’t go by yourself anymore.’”

But Eric persisted, right up until he failed to return from one solo trek in a place far from home.