Signboards at trailheads all around the Uinta Mountains urge visitors to “leave no trace.” Since the 1930s, the core of the Uinta range has received special protection, first as a “primitive area” and later as a Congressionally-designated Wilderness.

Hikers, hunters and horse-packers who travel through the High Uintas Wilderness are urged to practice a special form of outdoor ethics, to “take only photographs and leave only footprints.”

That approach helps preserve the wildness of the High Uintas for future generations, but it also complicates the task of finding a wilderness traveler, like Australian trekker Eric Robinson, when something goes wrong.

Marilyn Koolstra travels to Utah

In episode 3, Eric’s wife Marilyn Koolstra described learning that her husband failed to return from his solo trek on the Uinta Highline Trail. Within a couple of days, Marilyn and her daughter, Rachel Marsden, were on a plane bound for the United States.

“It was not an easy trip,” Marilyn said. “It was long across the Pacific.”

Worse yet, Marilyn and Rachel’s last-minute booking meant they were not seated together. Surrounding them in the passenger compartment of the plane were a group of rowdy young Australian men headed to Las Vegas, Nevada for a bachelor party.

“It was hard,” Rachel said. “You’ve got that sense of time passing and it dragging super slowly, with this sense of urgency of wanting to be there.”

Flying eastbound across the International Dateline meant that Marilyn and Rachel’s long flight across the Pacific took off and landed on the same date. Both mother and daughter felt a sense of disorientation upon arriving in Los Angeles, then making their connecting flight to Utah.

One of Eric’s hiking friends, Devon McClive, picked Marilyn and Rachel up from Salt Lake City International Airport and drove them to a house in the ski resort community of Park City where they would stay for the duration of their visit.

“Devon was filling in what had happened so far,” Marilyn said.

Another of Eric’s hiking friends, Julia Geisler, was out with her partner Blake Summers looking for Eric in the High Uintas Wilderness. The Duchesne County Sheriff’s Office had its own search and rescue teams out as well.

Marilyn Koolstra’s TV interview

Marilyn found herself struggling to make sense of everything happening related to the search.

“I’m probably a little big jet-lagged, certainly traumatized to a point of maybe not clearly thinking about the whole process yet,” Marilyn said.

She’d hoped to head straight to the search command post, but was unable to get in touch with the Duchesne County Sheriff. Instead, Eric’s friend Devon suggested Marilyn speak with the local news media.

“Rachel and Devon sort of persuaded me that was the best way to reach out to the most number of people,” Marilyn said.

Still, Marilyn felt reluctant. She’d been trained in her professional role as a school teacher and administrator not to speak directly to the press. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade had also supplied her with a pamphlet that urged caution in dealing with the American news media.

“So I was a little bit cautious,” Marilyn said.

She agreed to sit for an on-camera interview with KSL-TV. Her daughter, Rachel, watched as Marilyn fielded questions about her relationship with Eric and her feelings about his disappearance.

“She sat there and spoke with her whole heart,” Rachel said. “This felt like real action, particularly having her there to speak to, ‘Hey, this is my husband. This is our family member. Yes, he’s an Australian but please help us.’”

The final photograph of Eric Robinson

Marilyn’s courage in speaking out had an immediate impact. On that same day, Thursday, August 11, 2011, a man named Carmie Hull contacted the Duchesne County Sheriff’s Office to report having seen Eric at Fox Lake on Saturday, July 30.

“[Hull] indicated that he spoke with Eric Robinson and he seemed to be in good sprits [sic] and excited to finish his hike,” Duchesne County Chief Deputy Dave Boren wrote in an official report.

Hull provided Duchesne County with two photos he’d taken of Robinson, showing him squinting into the morning sun while holding a mug of tea. The sheriff’s office distributed the photo to the news media, in the hopes of generating additional tips.

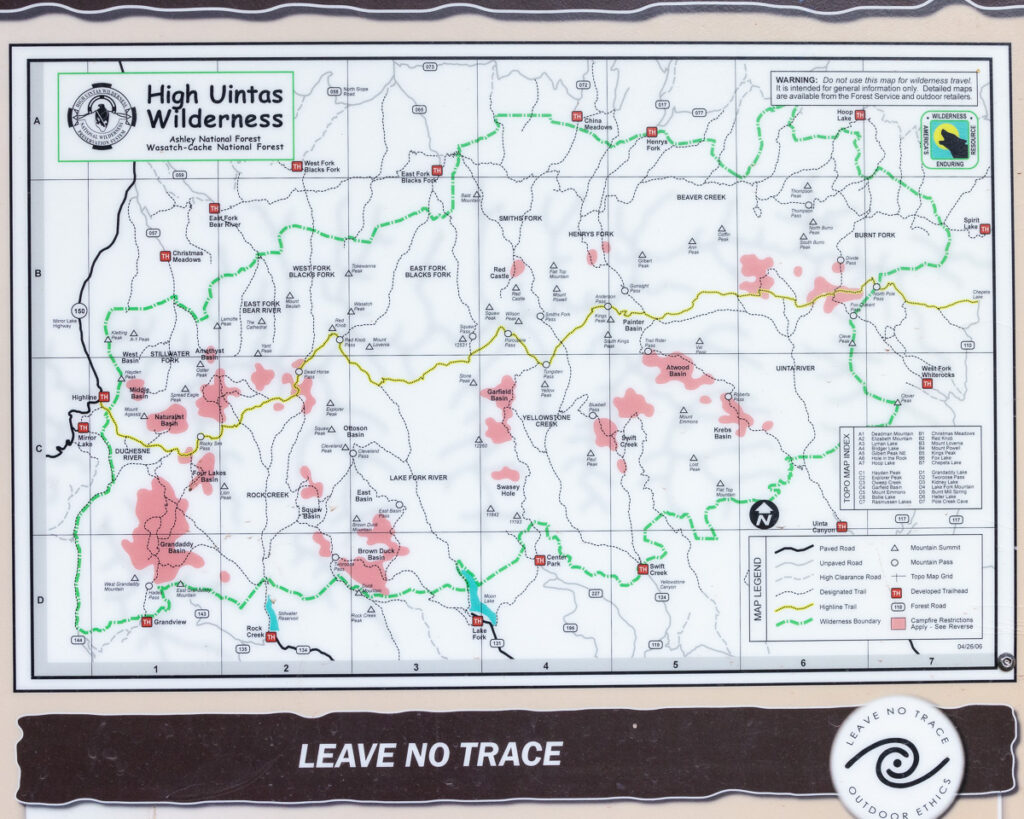

That sighting of Eric was very stale, nearly two weeks old. It helped narrow the search area, but not by much. Fox Lake sat near the eastern edge of the High Uintas Wilderness Area. Eric had planned to exit from the western edge, at the Highline Trailhead on the Mirror Lake Highway, roughly 60 trail miles distant.

Access to all points in between was complicated by a lack of roads. Searchers heading into the area to look for Eric had to either walk long distances, take horses or by flown in and out by helicopter.

New Roads to the Uinta wonderland

Only two paved roads cross the Uinta Mountains today. Utah State Route 150, also known as the Mirror Lake Highway, crosses the far western edge of the range and is the primary recreational access for many people visiting from Salt Lake City.

U.S. Highway 191 sits near the eastern edge, connecting Vernal, Utah to Rock Springs, Wyoming. To understand why no paved roads cross the Uinta crest between these two points, one must look a century back in time.

Public awareness of the Uinta Mountains began to grow following World War 1, when a surge in vehicle ownership allowed people to more easily explore areas farther from home. Against that backdrop, the U.S. Forest Service proposed constructing a road into the “Grandaddy Lakes” region of the Uinta Mountains.

Newspaper publishers seized on the idea, with writers penning articles full of superlatives about the “limpid lakes crystal in their settings of verdure” and other attractions of the infrequently visited Uintas.

“Accessible all this is now only to the intrepid wanderer who goes out into the open and braves inconveniences and even dangers,” J.R. Kennard wrote in an October 7, 1922 article for the Deseret News.

Article from Oct 7, 1922 Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah)

The road proposed by the Forest Service would allow vehicles to access high terrain dotted with lakes and covered in thick pine forest, at that time still relatively untouched by human impact.

“What if this riot of the big outdoors were made available to all who dwell in crowded places,” Kennard wrote. “It has been said that the canyons the route would make available would furnish sites for summer homes illimitable—a first class summer home site for every family in Utah and plenty of room for New Yorkers.”

The Forest Service and Utah State Road Commission began construction on that road in 1923. The first section, completed two years later, followed the course of the Provo River to its headwaters. In the years immediately following, the road was extended to Mirror Lake, at the headwaters of the Duchesne River.

This road was the precursor to the modern Mirror Lake Highway.

Birth of the Uinta Wilderness

Opposing forces were developing within the ranks of the Forest Service during this time. A growing number of rangers, including some with prominent voices such as Aldo Leopold, advocated for a more conservation-minded approach to forest management.

Forest supervisors overseeing the Uinta Mountains foresaw a bleak future where all of the range’s high-elevation meadows might be pierced by roads. To counter this, they proposed the creation of a “primitive area” protecting the core of the range. Motor vehicles and road building would be banned within the bounds of the primitive area.

In September of 1930, a Forest Service official named R.H. Rutledge led a party on an 8-day trip to define and survey the boundaries of the proposed primitive area. Rutledge invited his 19-year-old daughter, Dorothy Rutledge, to accompany the group on horseback.

Dorothy Rutledge wrote an account of the experience, and portions of her story were published in the Deseret News and Ogden Standard-Examiner newspapers.

“Acquaintance with the High Uintas is a priceless experience,” Rutledge wrote.

The party traveled counter-clockwise from Mirror Lake, through the Grandaddy and Brown Duck Basins to Moon Lake. There, the group resupplied before heading east and north, up the Yellowstone River to the foot of Kings Peak, the highest point in Utah.

“That night the water froze in the water bucket, and my chaps turned white with frost,” Dorothy wrote.

From that point, Dorothy and the others traveled west along the path of the modern-day Uinta Highline Trail, crossing Porcupine and Red Knob Passes before camping in the West Fork Blacks Fork drainage, at the foot of Dead Horse Pass.

“When I thought of the five horses that have rolled to their death down that slope, I was not a little worried,” Dorothy wrote. “The trail soon got so dangerously narrow and steep that we dismounted and led our horses the rest of the way.”

Article from Sep 28, 1930 The Ogden Standard-Examiner (Ogden, Utah)

The expedition, and Dorothy’s article, proved to be a public relations success. The U.S. Forest Service formally created the High Uintas Primitive Area in 1931, barring further road construction in the heart of the range. Those protections were strengthened, and the area covered by them expanded, with the signing of the Utah Wilderness Act of 1984.

Eric Robinson versus the High Uintas Wilderness

The wildness of the High Uintas drew Eric Robinson halfway around the world to walk that same path. But the dangers Dorothy Rutledge highlighted in her 1930 article were much the same by the time Eric arrived in 2011.

Forest Service signs today warn visitors to expect “the challenges and risks of changing weather, rugged terrain, and other natural hazards” within the High Uintas Wilderness Area. Eric carried what he believed were the necessary tools to deal with these challenges and hazards. His family knew him to be competent and experienced in mountain trail.

Marilyn Koolstra explained all of this in her TV news interview just hours after arriving in Utah to join the search in 2011.

“It’s a bit hard to remain positive after four days, and knowing the kind of person that he is,” Marilyn said. “When I think about it, I can go to the dark side. What if, and where is he and what’s happened?”