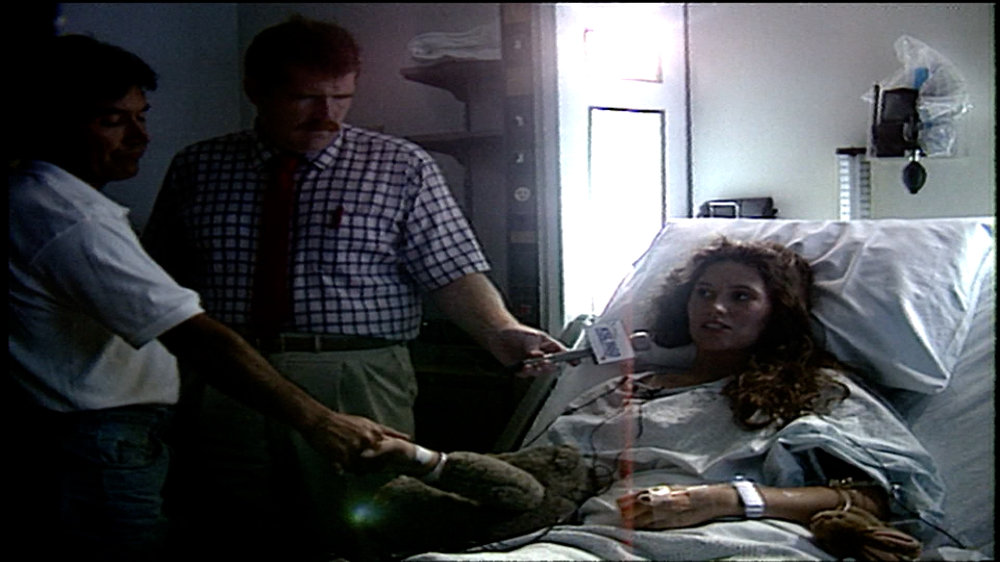

Photo credit: KSL TV

SALT LAKE CITY — Yvette Rodier willed herself not to move as the man who’d emptied a gun into her body shoved his hand into the pocket of her jeans.

She realized she needed to stop screaming and pretend to play dead when the initial burst of gunfire stopped, and she heard him reloading the gun. The 18-year-old fell on her side next to her date, Zach Snarr, as bullets ripped through her side and her leg. After he reloaded, he fired at her head.

Then, as suddenly as the shooting started, it stopped.

She heard footsteps toward them, and she held her breath. Zach lay motionless beside her.

Yvette’s eyes were open, and she saw the shooter’s, felt his breath on her skin as he searched their pockets. She swallowed fears about what he might be looking for or what he might do.

On a second search of Zach’s pockets, he found what he was looking for — Zach’s keys. He ran toward the parking lot of LIttle Dell Reservoir where they’d parked just a few minutes earlier to unload the camera equipment they planned to use to take pictures of a rising full moon over the water.

Photo credit: Scott G. Winterton, Deseret News

Yvette exhaled.

It smelled like something was burning. She tasted metal. Her head felt hot, her body tingled.

“It felt like I was sweating, but that was blood,” she testified in the preliminary hearing in February of 1997, just seven months after the shooting that killed one of her best friends and changed the course of her own life.

Yvette didn’t move until she heard the Bronco drive away, and then she called for help.

“Help!” she yelled. “We’ve been shot!”

A woman’s voice responded.

The woman said something about going for help. Yvette laid in the silence but not for long. She didn’t know why they’d been shot. She didn’t know if he’d come back.

She called Zach’s name. He didn’t answer.

She tried to stand up, but her right leg wouldn’t support her.

“I didn’t know what else to do,” she testified. “But I knew I had to get help, and I knew that … it would have taken a long time to go back up the asphalt, then over to the road, and I knew that the road was above me, so I knew that I could go up the hill.”

What she did to survive the night of Aug. 18, 1996, still shocks the detective who led the investigation of the shooting.

Photo credit: Andrea Smardon

“We came back a couple times to photograph both at night and during the daytime just to get that different perspective,” said now-retired Salt Lake County sheriff’s detective Keith Stephens. “And it was … it was just unbelievable. … Just like … did this really happen?”

And that was just the beginning of how Yvette’s determination to reclaim her life would impress and inspire those lucky enough to know her.

“It was superhuman,” he said, stopping to fight back emotion. And that continued, he said, throughout the investigation. Yvette accommodated every request from police or prosecutors, and even the media.

“She was extremely selfless,” he said, his voice quivering. “She put all her injuries aside to help with the investigation. … She was very eager to help, very eager to, in her own way, speak for Zach.”

Yvette’s fight for her life would only become more complicated in the months and years after her miraculous survival. And it began from the moment she woke up in the hospital with her mother sitting next to her.

“I just know Zach’s dead,” she said. “I don’t, I don’t know how. But I’m sure of it.”

Later that morning, the Snarr family gathered in her room.

“And Sy came to me very first and hugged me,” Yvette recalled, referring to Zach’s mother, Sy Snarr. “And she leaned in and just said, ‘I’m so glad he was with you, because I know he was happy.'”

Gratitude and guilt washed over Yvette.

“I remember … those words daily,” she said softly. “And it was such a gift that they would take that time and come and visit me and tell me that, you know, especially the day after their son’s been killed.”

Sy Snarr knelt next to Yvette, her grief so heavy, she couldn’t even stand.

Yvette took her through every detail of Zach’s last night from where they went to dinner to the fact that he’d expressed so much pride in the fact that his mother had made the quilt he’d spread on the ground.

Photo credit: Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office

“I don’t know why it mattered, but I never would have known,” Snarr said. “I had taken him to lunch there a few days before — Zach and I, just the two of us — and he liked it, and I think that’s why he took her there, but I was glad to know that.”

What Yvette couldn’t share was how she felt guilty about surviving when Zach did not.

“When I was on the side of the road, and I had left Zach to get help,” she said. “I think I started feeling guilt at that moment that I wasn’t with him. And that he likely had died and I didn’t.”

Photo credit: Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office

Yvette’s road to recovery was brutal.

First, there were the physical injuries. No one could tell how many times she had been shot because she also sustained injuries from the shrapnel created when the bullets hit the tripod. She suffered hearing loss, memory problems, and for months, she had a severe limp because her leg was so badly injured.

“I was hit several times in the head, so there was a lot of blood and damage to my skull,” she said. “He used hollow tip or hollow point bullets. And so one of them hit my left side in my back and went all the way through and got lodged in my left inner thigh. One hit my left side and just totally expanded and blew up the left side, just opened it up raw. And then one more along my shoulder.”

“And it was like, she is going to be OK, but boy, she’s got an ugly road ahead of her,” said her aunt Toni Sullivan. “She really had some very serious, critical injuries. And it was clear that there was a major road ahead (for) her recovery.”

Almost more daunting, however, was the recovery she’d face from wounds most people couldn’t see.

“There were many changes,” Sullivan said. “She became more withdrawn. … For many years, and to this day, she suffered survivor’s guilt. … She was always fearful, and she’s suffered a lot of nightmares … for years and years and years because she would say she could still feel his breath when she’d be asleep.”

Sullivan described how Yvette’s mother, Linda Dart Rodier, who died in 2018, had to clean and treat the gaping wound on her daughter’s side every day.

“That was really difficult for Linda,” Sullivan recalled of her sister. “Initially, it was really difficult to realize she was sticking her (hands) all the way through her daughter’s body.”

Yvette said she continued to struggle with memory loss, hearing loss and nightmares. She couldn’t be alone, and she was terrorized by even the sound of gunshots on TV.

Still, she was determined to reclaim her life. She attended classes at the University of Utah as she’d planned, and she began dating.

Yvette didn’t get to choose what happened to her. But as she worked to heal herself and reclaim her life, she’d find immense gratitude for her ability to choose her path.

“I think that’s the best part about not having any choice in this is that afterward, then I have all the choices,” she said. “I didn’t have a choice. Zach didn’t have a choice. But once I lived, and I’m coming out into society, I have all the cards, I have all the choices. So I’ve been trying to think of it in that way that these are really cool choices I get to have, because of something horrible, but I still have choices.

Photo credit: Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News

“So it’s, I feel powerless to the emotional pain. But as far as moving forward, I feel empowered to be making choices.”

And among those choices she made as she rebuilt her life was to never say the name of the man who shot her. She has held fast to that choice, and it has helped her feel safe.

But more than two decades after that terrifying night, she’d be faced with a choice that would challenge her decision to erase him from her life.