Photo credit: Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

SALT LAKE CITY — As soon as Liane Bell saw her mother’s friend, she felt her anguish.

“Real pain,” Bell said, a sob choking her voice. “Real intense pain. And I have questioned since — I don’t know how she moved about, really. I don’t know how she physically was able to leave her apartment and get in our car and go to church after hearing and knowing the intensity, the severity of what had just happened with her son, what he had done.”

A mother’s pain

Bell was getting her five children ready for a church service the morning of Sept. 1, 1996, when her mother called and asked for a favor.

“She said, ‘Nelida’s son has committed a horrible crime, and all that Nelida wants to do this morning is be in a place where she can partake of the sacrament to bring peace and comfort to her soul,'” Bell recalled. Her mother explained that her friend’s son had shot two young adults, killing one and gravely wounding the other, just a few days earlier.

And then she asked her daughter if she’d take the woman to church with her family in hopes of finding a few minutes of peace.

Bell wasn’t sure what to say or do for the woman whom her parents had met while serving a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New York City a couple of years earlier. The woman, Nelida Benvenuto, had three children, and shortly after Bell’s parents returned to Provo, Utah, Benvenuto moved to Utah, hoping to give her children the kind of support they lacked in New York.

But less than a year after arriving in Utah, her youngest son had done the unthinkable. On Aug. 28, 1996, he shot two 18-year-olds he’d never met — Yvette Rodier and Zachary Snarr. Rodier survived, but Snarr was killed. Jorge Benvenuto, 19, was arrested a day later at a gas station in Lehi as he attempted to walk to his brother’s house in Provo.

Bell’s parents said their friend was devastated by what her son had done. She hoped for relief from the suffocating pain in a sacrament meeting.

Bell and her husband drove Nelida Benvenuto to their home, where they asked her to join them in a family prayer before they left for church.

“Nelida joined us, but she hadn’t said anything yet,” Bell recalled. “You know, I just wonder if the heavens felt a little closed to her at the time. … We knelt in prayer and just asked for comfort, and that peace would be found somehow in the meeting. And then we got in the car and drove to church.”

The woman wore sunglasses, even in the building, and said very little.

“She just shook her head a lot and tears flowed very easily,” Bell said, adding that she prayed, but admitted she wasn’t even sure what to ask for. “I just didn’t even know where to begin in a prayer. It’s just too huge. … I was just so sorry for her. And what could I say that would even bring her peace at that moment? Nothing.”

That Sunday happened to be the first Sunday of the month, which meant it was fast and testimony meeting. For those of the Latter-day Saint faith, that meant instead of a pre-planned sermon, anyone in the congregation could come to the pulpit and share their testimonies, thoughts or feelings.

But instead of the usual discussions of faith or doctrine, a succession of teenage congregants walked to the pulpit to share something else — pain.

“They were standing to just shed their emotions of grief,” Bell said, fighting to control her own sadness at the memory. “One by one these youth stood up crying and crying and expressing emotions of, ‘I can’t understand why this happened. … Why do we have to endure this in our lives, we’re kids.’ Just heavy, heavy emotional testimonies.”

And as each teen stood in front of the microphone, the woman sitting next to her squeezed her hand.

“The mother of this killer, which the youth had no idea was sitting right next to me on the bench, listening to how her son had changed these … lives forever,” Bell said, tears flowing freely down her cheeks. “And she started squeezing my hand, and just saying, ‘I can’t do this. I can’t do this.” As one more youth would walk up, she would look and just, ‘I can’t. I’ve got to leave. I can’t go through this anymore.”

But they sat, frozen in pain, afraid to call attention to themselves if they left, as members of the congregation shared their disbelief, their memories, their pain.

“So she endured,” Bell said, sobbing. “I don’t know how she did that. She endured an hour meeting, at least, of hearing of the grief that her son had just caused this student body.”

Bell took her home as soon as the meeting ended.

“It was just Nelida and I in the car,” Bell said. “Nothing much was said. … I remember saying, ‘Nelida, I know that you will find a purpose in this someday. And you will find comfort eventually in your life.’ And of course, she didn’t respond. I don’t even know if words were heard at that point. She just wanted to get home really quickly.”

Bell found herself wondering off and on over the years why Benvenuto ended up in that particular church meeting. It seemed an unfortunate twist of fate, even cruel.

But she has since also found herself consuming news differently. Anytime she reads or hears about a tragedy, she always thinks about those who loved the person everyone else hates.

“I always think of family members,” she said. “I always think of mothers, when I hear statements from them later of apologies, or we just don’t know how this happened. We are so sorry. … I just feel like they don’t even have the adequate words to express their pain for the pain their child caused.”

The email

And then a few years after Bell’s mother died in 2014, she received an email from Nelida Benvenuto.

“She said that Jorge had written a letter to the victims, and that he wanted someone to … hand deliver … this letter to the Snarr family, and would I be able to do that? Would I be the person that would hand deliver the letter.”

Bell imagined herself on the Snarrs’ porch.

She wondered what she’d say after they answered the door. She wondered how they’d feel about hearing from the man who had murdered their son.

“I thought about it,” she said. “I prayed about it. I didn’t feel like I had received any kind of reassurance or answer. So I told Nalida, ‘I don’t think I can do that. I just … I want to watch out for the victims first. And that’s great that Jorge has a letter of repentance, but I’m not I can’t find a way yet.'”

But a year later, she realized she and Snarr’s mother had a connection — her cousin, Karen Fairbanks. She asked her cousin if she thought Sy Snarr would want a letter from Jorge Benvenuto. Her cousin promised to ask.

At an annual holiday dinner in 2018, Fairbanks told Sy Snarr about the letter Benvenuto had written.

Photo Credit: Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

“I said, ‘I’ve waited 22 years for that letter,'” Sy Snarr said. “Every Aug. 28, every single Aug. 28, I think, ‘Does he know what today is?’ You know, does he even think about Zach? Does he care? That had always been in my mind. And so I said, ‘I want the letter.'”

Once Bell received the letter via FedEx, she invited Sy Snarr to her house. And in the same living room where she had knelt with Nelida Benvenuto all those years ago, she handed her a letter from the man who killed her son.

“I said, ‘I don’t want to read it now,'” Snarr recalled. “I want to read it with Ron.”

The two women talked about a number of things, and Bell told Snarr about that church meeting all those years ago.

“I can’t imagine what that was like for her,” Snarr said of Nelida Benvenuto. “What are the chances? I can’t imagine how hard that was for her, and Liane said she was just shaking and had her sunglasses on. … My heart really went out to her at that point. You know, how awful for her.”

‘A beautiful letter that changed everything’

Snarr said it was surreal to hold a letter from her son’s killer in her hands.

“I used to think, ‘I wonder if he’d ever even write a letter or something,'” she said. “I never thought it would happen.”

When her husband, Ron, returned home from work, they sat together and read the letter. Empathy washed over them.

“I thought to myself, ‘Well, everybody makes a mistake … and he made a terrible mistake,” Ron Snarr said. “I just kept thinking of Jesus — forgive them for they don’t know what they did. He wasn’t, he didn’t know what he was doing. … I’m trying to have the spirit of Christ in me, you know, and forgive one another as you’d have them forgive you … and I’m feeling the tap on my shoulder is what I’m feeling.”

He laughs to himself at the thought of his son tapping him on the shoulder, as Zach used to do, reminding him, even from the grave, of what was right.

“He’s all over it,” he said of his belief that his son had something to do with the letter reaching them. “He was just an exceptional human being. He was.”

The simple, hand-written letter created a beautiful but fragile refuge from the pain Sy and Ron Snarr had endured for more than two decades. Sy Snarr, especially, became fiercely protective of this new and unique relationship. At first, they were very careful about whom they told about the letter and the transformation it had wrought in their lives.

The one exception was their children.

Photo Credit: Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News

The next day, Sy Snarr read it over the phone to her oldest son, Trent, who lives out of state, and to Sydney, who lives about 20 minutes from her parents.

“I called Sydney and I said, ‘I want to read you this letter’,” Sy Snarr recalled. “And she said, ‘Well, I don’t know if I want to hear it.’ And I said, ‘You need to hear it.'”

Sydney Snarr Davis said she’s not sure she’d have accepted the letter if it hadn’t come from her mother.

“She started reading it to me,” Davis said, “and by the end of the first paragraph I was crying and my hands were shaking, and she finished the letter, and it was just silent for a minute. And I said to my mom …”I needed to hear that; I can breathe for the first time in 24 years. Like, I could take a deep breath and not feel that crack … in my heart.”

Sy Snarr said there was a long silence after she read the letter to Trent Snarr.

“And he was emotional, too,” she said. “And he said, ‘The whole thing is just so incredibly sad to me.’ … But that letter was so … I felt his sincerity. He made no excuses. He didn’t ask for forgiveness. Nothing. He just, it was a beautiful letter that changed everything.”

Sy Snarr has likened her grief and anger to a backpack full of rocks. She had taken many steps to lighten her load by setting down some of that anger and resentment. But Jorge Benvenuto’s letter to her family emptied that metaphoric backpack of rocks she hadn’t even realized she was still carrying.

“When I read that, every last little rock, pebble is gone. It’s gone. … And you know, I don’t know what his life has been like. … I listened in court, but I thought they were just making excuses. … But you know, I don’t know what caused him to do it. But I know that he has sincere regret about what he did. And he’s taken full, full responsibility.

“It really impresses me that he didn’t put the blame on anyone else or something that happened to him. … He didn’t ask me to forgive him. He just said, ‘I’m so sorry. What I did was wrong. And please don’t blame my family.’ And that, that really touched my heart right there, that touched my heart.”

‘I felt like he was in my house’

Sy Snarr learned that Benvenuto had also written a letter to Rodier, who survived the attack. She reached out to her to see if she might be open to receiving a letter from him.

“She told me about the letter,” Rodier said. “She told me how beneficial it’s been for her.”

She was surprised that Benvenuto had written the letter and shocked that the Snarrs wanted to hear from him.

“I would never think that she would want to hear from him,” she said. “But I love that for her.”

Rodier said she could tell that the letter had helped Sy Snarr immensely.

“I could tell it brought her a lot of … I don’t know if she used the word peace, but that’s the feeling I got, is that she felt peace with it, and it has been very helpful for her,” Rodier said. “And she’s so glad she got it.”

When Sy Snarr mentioned that Benvenuto had a letter for her, Rodier said she sobbed.

“I think it was partly because I don’t think about him,” she said. “And then he was suddenly in my house. Essentially that’s how I felt. I felt like he was in my house at that minute. And so I just cried.”

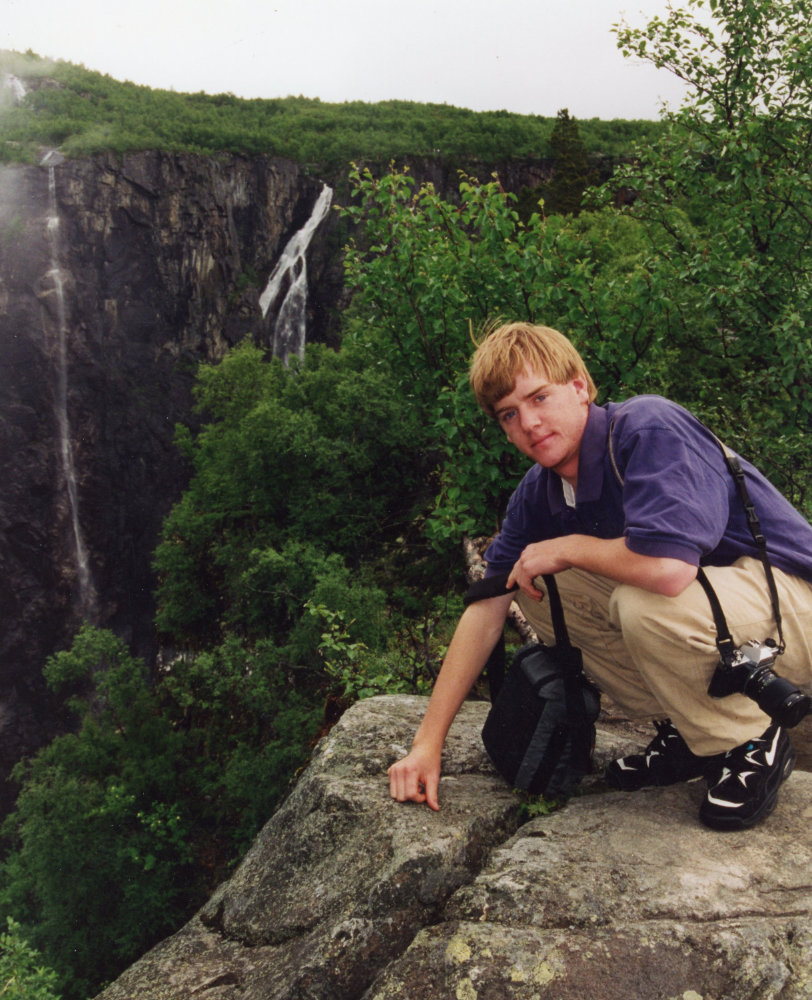

Photo credit: Snarr family photo

Rodier said she was overwhelmed, and she told Snarr she needed to think about it. She couldn’t even put her feelings about the offer into words for several days.

“I tried to figure out how I was going to present it to him,” she said of why she didn’t tell her husband right away. “Not because it was anything bad, but just I had to put the words to what it was and what I was feeling. … When we did finally talk about it. He was intrigued. He had questions that I didn’t have answers for. And then we just kind of went back and forth on pros and cons about why it would be good or bad.

“And the end for me was I didn’t want to give him that relief that he’d given something to me that maybe helped me. Which sounds really mean and a little bit vindictive. But he can write the letter. … But I feel like my receipt of the letter would give him some sort of comfort that I don’t feel he deserves.”

Rodier said she isn’t consumed with anger at the man who shot her. She also doesn’t want him in her life — in any way.

“The way I feel about him is very neutral,” she said. ” I’ve never been angry at him. I feel like probably because everyone around me was so angry at him, that it was easy for me to just let them be angry. I’ll deal with my own stuff and they can be angry. So I don’t have any extreme feelings about anything toward him. I guess except that I don’t want him to feel comforted by something I’d do for him.”

Total forgiveness

The Snarrs feel their son has had a hand in what’s happened. Sy Snarr sat down and wrote Benvenuto a letter.

“I did write him back,” she said. “And I told him without a doubt, I knew Zach had forgiven him immediately.”

She admits it took her a bit longer to follow her son’s example.

“And my forgiveness is sincere,” she said. “I have totally, totally forgiven him.”

But what Sy Snarr was about to learn is that forgiveness wasn’t an ending.

It was, as she would learn, the beginning of something else entirely.