SALT LAKE CITY — Carla Maas was lost in a haze of grief until she looked up from the witness stand and saw his face.

“I remember seeing Michael Moore across from me,” she said of her husband’s killer. “And him just looking at me, and it kind of — it scared me. It made me very nervous. … I saw no remorse.”

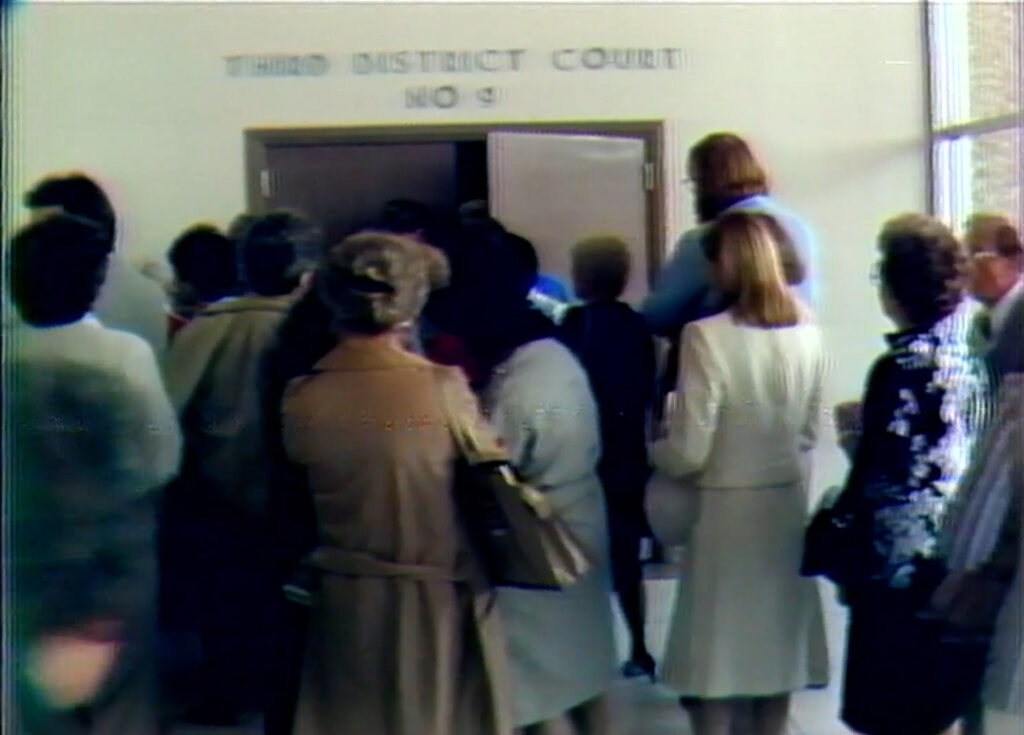

The austere, windowless room in Utah’s 3rd District Courthouse was packed. People sat on the floor in the aisles and stood along the back wall. Maas had huddled in the center of her extended family, hoping to avoid the swarm of media that threatened to pull her from the safe obscurity of her now shattered life.

“I felt like I was being closed in on,” she said of walking to the witness stand during Moore’s capital murder case. “I don’t like to be in front of crowds. I don’t like to be the center of attraction. I like to hide in the back of the room.”

But on this particular morning, Sept. 8, 1982, Maas left the safety bubble her family created for her to do one thing — make sure the jury saw her husband as more than the body of a delivery man in the back of a van.

“I remember the bag that they brought out with all the evidence in it — my husband’s clothing,” Maas said. “And it was bloody.”

The prosecutor asked if she recognized the brown, blood-soaked shirt. She saw the name “Bud” stitched on the chest and she felt sick.

“I was shocked,” Maas recalled. “I was devastated. I put my head down, and that’s when I started feeling light-headed, dizzy. … It was really tough. And all I could do was cry.”

She said Moore just stared at her as she sobbed.

Moore was manager of the iconic Log Haven restaurant when he confessed to killing 32-year-old Jordan Rasmussen, alleging he was being forced to embezzle by a network of organized crime associated with one of two men who bought the restaurant in 1979. Buddy Booth was killed simply because he happened on the murder scene while Moore was trying to decide how to dispose of Rasmussen’s body.

Moore’s defense attorney, Bob Van Sciver, told the media, “It’s an awful, brutal crime. I think (there’s) little that can be said in justification for having committed that much carnage.”

But Van Sciver, who died in 1997, was also convinced this wasn’t a death penalty case. And, using the same facts that prosecutors hoped would convince jurors to send Moore to the firing squad, the defense painted a completely different picture.

It all began with two young widows — Maas and 30-year-old DeAnn Rasmussen — trying to make their dead husbands real for a jury who could only see 25-year-old Michael Moore.

Both women cried as they talked about Booth and Rasmussen. They were devoted fathers who valued their families above all else.

As tears streamed down Maas’ face, her sadness slowly hardened into something else.

“I was angry,” she said. “I was furious … because why would he kill an innocent man? … I could see that he was quite cold.”

Through her tears, she met his stare. And then she made it clear what punishment she felt he deserved for robbing her children of their father.

“And I did say an eye for an eye,” she said. “I didn’t think he deserved to be on this earth for killing two people. I just felt that he deserved to die, as well.”

A tragic case

Mike Carter was a crime reporter for the Salt Lake Tribune in 1982 and he remembers his phone ringing on that frigid winter morning.

“I remember this particular morning because it all happened really early,” he said. “I actually got a call at home … from one of the detectives telling me that there had been a double homicide up Millcreek Canyon. So I drove from home up there.”

The road was blocked, but that didn’t deter Carter. He parked his car on the side of the narrow canyon road and hiked through the freshly fallen snow to get a look at the gruesome scene in the driveway at Log Haven. He was only there a few minutes before the homicide sergeant yelled at him, so he went to the detectives’ offices and that’s where he began to learn what happened.

“They didn’t really know what was going on yet, other than it looked like an employee had killed his boss,” Carter recalled. “And that Buddy Booth was unfortunate in that he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. … They were able to put that much together that quick.”

By the end of the day, Moore confessed to the killings. A few days later, prosecutors filed capital murder charges against the 25-year-old, and his family hired one of the state’s most effective and flamboyant defense attorneys.

Carter said there were a number of great attorneys in Salt Lake City in the ’80s, and Van Sciver was one of the best.

“He had the greatest comb-over of all time,” Carter said laughing. “He had this big head of shocking white hair, which was thinning a little on top, and it was combed back in this bouffant kind of thing. He was tall and talked faster than anybody you’ve ever met in your life. But he was a terrific attorney.”

Van Sciver made his mark on the legal system by taking some of the toughest cases with a fearlessness that made him a champion — and a challenge. The one thing no one ever accused him of was being boring.

In his opening statement, Van Sciver conceded the basic facts of the case were undisputed. But, he said, there was an explanation for what Moore had done — and it meant he wasn’t guilty of premeditated, cold-blooded murder.

“This particular trial … I remember it being very dramatic,” Carter said. “There were a lot of surprises. … And juries weren’t tentative about handing down the death penalty in those days.”

Van Sciver said what happened the morning of March 5 was the horrific crash of an emotional spiral. Moore essentially operated in an alternative reality where he was losing the thing he loved most — the restaurant he managed.

The weeks leading up to the shooting were littered with evidence of Moore’s emotional deterioration. He told friends, co-workers and employees at other businesses that the “Chinese mafia” was out to get him, or wanted to set him up.

And it all began when the two businessmen who owned the high-end restaurants decided their partnership had devolved into acrimony. They decided the only solution was a business divorce.

The split was scheduled to be finalized that very day — March 5, 1982. And Rasmussen was supposed to take over Moore’s job as manager. But it’s unclear if that was ever officially revealed to the staff — until one of the owners told police after the murders the new owners planned to replace most of the staff.

Van Sciver said Moore had “no sleep, no food, some alcohol (the night before)” and he was losing a job that “appears to have been his entire life.”

Moore told friends he was afraid he was going to be set up for the thefts by the mafia. He said his phones were tapped, and he’d been told “hatchet boys” were coming for him.

Prosecutor TJ Tsakalos said investigators never bought Moore’s twisted version of events. And neither did he.

“I couldn’t get into his head as to why he was thinking the way he was thinking,” Tsakalos said. “Over the course of the trial, people talked about him and how bright he was and how accomplished he was. … I came up with the term chameleon. I thought he could change colors to manipulate you. … So my theory was, he made it up to try to justify what he did.”

The confession

The centerpiece of proving Moore deserved the death penalty was his confession given to police the afternoon of the murders. Prosecutors decided to play the entire 60-minute recording during the trial.

For the families, it was the first time they heard a detailed breakdown of the brutality of the killings. He methodically walked through how Jordan yelled, “No, Mike!” as he shot him in the head, and then how he frantically searched for chains so he could sink Rasmussen’s body in the sump, where they disposed of grease, garbage and sewage.

It was the first time they heard how Booth was leaning over Rasmussen’s body when Moore came running out of the restaurant, and how he turned to run just as Moore shot him twice, hitting him in the arm and the back. He fell face-down in the snow.

And then “he gave them the coup de gras,” Tsakalos said. “He shot them in the head after they were down.”

When asked why he shot Booth, a man he didn’t even know, Moore told police, “Dead men tell no lies.”

Listening to the details was too much for DeAnn Rasmussen.

“I was crying,” she said. “And I think it was at that point that they stopped the trial. And I went out of the room.”

Van Sciver moved for a mistrial, but the judge denied his motion. Rasmussen said every day of the trial was excruciating, but that day was almost unbearable.

“That was one of the hardest things of the trial when they (the defense) tried to say that Jordan had put himself in this spot that made it seem that he deserved it,” she said. “In fact, (Moore’s) words were, ‘He didn’t deserve to live.'”

Jordan’s three sisters left with her, all of them crying, trying to comfort each other.

“It was one of the hardest things I ever had to go through,” she said. “To go every day and listen to cold hearted Mike, his defense attorneys, defending him and trying to make Jordan look bad. It was gut wrenching. I remember coming home every night and just feeling so emotionally spent. I mean, it was hard for me to even think about getting up and going the next day, but you knew you had to.”

It was a Monday when the jury delivered a guilty verdict. And it was Wednesday morning when Van Sciver presented his case to spare Moore’s life.

The most emotional appeal came from Moore’s father, Edward Moore.

“I appreciate you giving me this opportunity to come and plead for my son’s life,” he said. “I want to also express Mike’s mother’s and my sorrow for the families, the Booths, the Rasmussens. … I say to the people in the jury, Mike’s a good boy. Don’t send us home today, Roseann and me, we have been suffering for six months not knowing whether we have a son or not. … I beg you, spare our son for one indiscretion or one transgression he did with his life.”

And then Michael Moore asked the jury to spare his life, promising that he’d do what he could in prison to improve the lives of those around him.

In his final plea to jurors, Van Sciver, living up to his colorful reputation, gave a graphic description of what imposing capital punishment meant. In 1982, Utah’s preferred method of execution was death by firing squad. Bob told jurors that if they sentenced Mike to death, he’d be “dragged from his cell one morning, his bowels will turn to jelly and his hands will be like clay. … We’ll strap him into a chair so we don’t miss, we’ll cut out a red heart and pin it over his heart … and on the command of ‘Fire!’ the life of Michael Patrick Moore will be removed.”

He told the jury no punishment was going to change what happened. “When this trial started, Jordan Rasmussen and Buddy Booth were dead. When this trial ends, they will still be dead. If you want to perpetuate the carnage of March 5, 1982, you can impose the death penalty.”

The jury took just 90 minutes to decide Moore wouldn’t face a firing squad. Instead, he was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences in prison.

Van Sciver was asked if his client felt any remorse for what he’d done.

“He does regret it,” Van Sciver told reporters after the jury’s verdict. “He can’t express it. Remorse is difficult for him to show.”

Ed Moore must have known this about his son because he tried to apologize to both widows. Neither of them said much, and both of them said it brought them no comfort. After the jury decided to let Moore live, Maas said she cried.

“I just remember how upset I was,” she said. “Because I wanted more. … Oh, I was glad that they said he was guilty. But then when they read the sentencing, that’s when I was upset. … I just didn’t think justice was done.”

Prosecutor John T. Nielsen, Tsakalos’ boss, said he was stunned. But he also thought, with two life sentences, Moore would never live free again.

“I thought, good for him,” Nielsen said. “Now, he can’t hurt anybody. I’ll go on to the next one.”

Nielsen, like the families, thought this was the end of their connection to Michael Moore. But they were wrong — all of them.