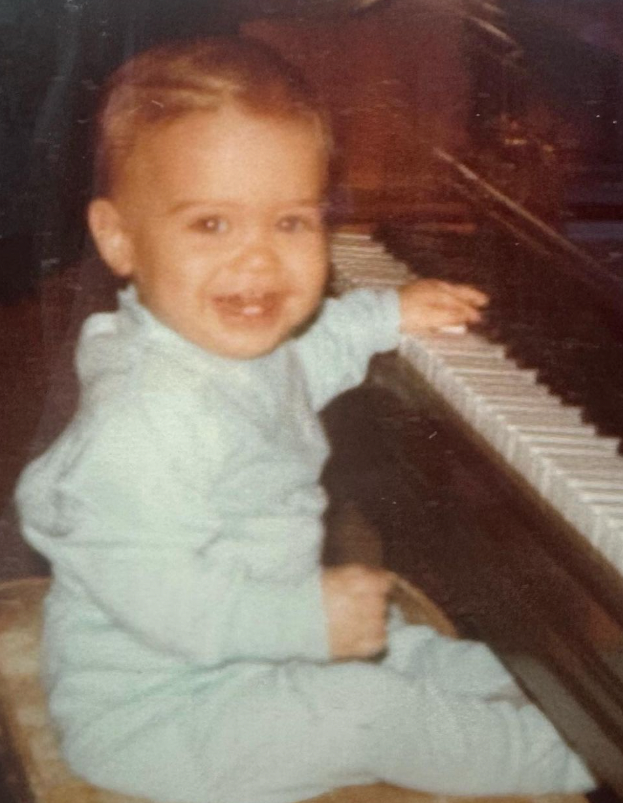

Episode nine of the true-crime podcast Ransom: Position of Trust tells the story of Hilton Crawford’s Execution and what happened to Carl and Paulette Everett.

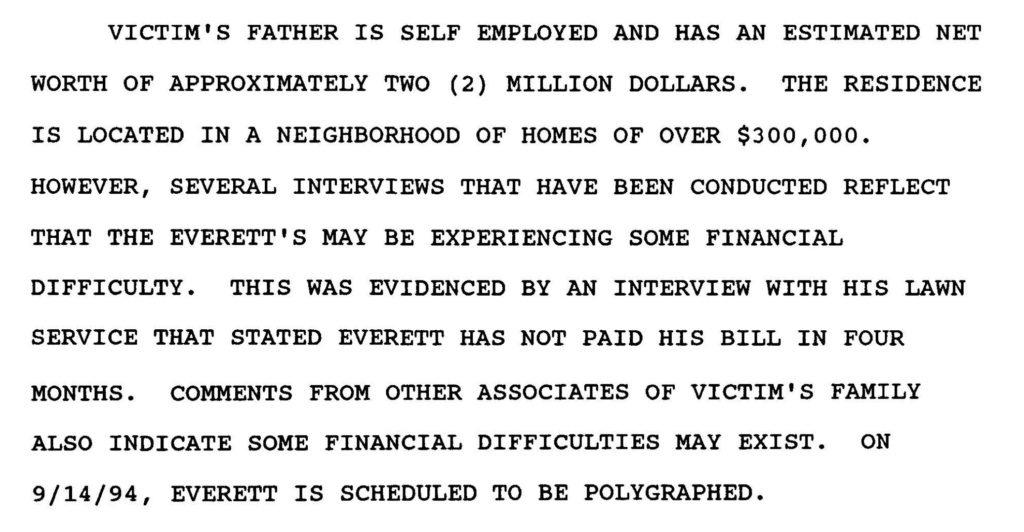

In the time between Hilton’s trial and his execution day, Paulette and Carl Everett were struggling. Paulette hoped that after the trial, their life would start returning back to normal but the grief was still overwhelming. Carl dove back into running his oil company, which often took him out of town.

“He’d come in the house, drop off the dirty clothes. He’d be there for just a little bit of time and then he’d just start sobbing. And he’d go pack up clothes and leave,” said Paulette. “He would disappear for long spans of time.”

And when he and Paulette would see one another, they weren’t on the same wavelength.

“He kept trying to get me to go to Amway meetings, and I finally just told him, I can’t do this. And so I began to stand back up on my own two feet and that didn’t please him.”

And while Paulette went to therapy to process McKay’s death, Carl refused to get professional help.

“He stuffed it. He didn’t talk about it, and deal with it, and learn how to cope,” said Paulette.

Instead, Paulette said, Carl turned to food for comfort: “He would eat and eat and eat and eat and eat.”

Carl and Paulette never figured out how to talk about the tragedy they’d been through. In 1999, Three years after the trial, and after 28 years of marriage, Paulette asked Carl for a divorce.

“It was tough. I didn’t want to divorce Carl, but I had no choice. I had to take care of me,” said Paulette. “And that’s what I learned too. We have to make decisions for our own lives that make no one else happy. And you’ve got to stand by what’s good for you.”

A Notice Arrives in the Mail

In February 2003, nearly seven years after Hilton Crawford received his death sentence, a letter arrived at Paulette’s door from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, informing her about Hilton’s upcoming execution.

Dear Ms. Everett:

This letter is to inform you that an execution date of July 2, 2003 has been scheduled for Hilton Crawford, #9992000.

Please advise if you or other family members desire to view the execution. There are five victim witnesses and three support person slots available, those accompanying you to Hunstville but not viewing the execution.

You may contact Karen Martin of the Attorney Gneral’s Office for information on Crawford’s appeals process at 1-800-983-9933.

Although Paulette had known that this day would come, she still hadn’t made up her mind whether she would attend. She didn’t know if seeing Hilton killed would bring closure or stir up more anger and grief.

Carl was also unsure if he wanted to attend. By that point Carl had remarried, and in the weeks leading up to the execution, he found out his new wife was expecting a child. When the press started calling him asking for quotes about the execution, he felt overwhelmed.

“He needed to get away, and we hopped on a plane and went on a cruise,” said Carl’s second wife Stacy Everett. “I think that he emotionally would not have been able to handle seeing Hilton Crawford again.”

Execution Day

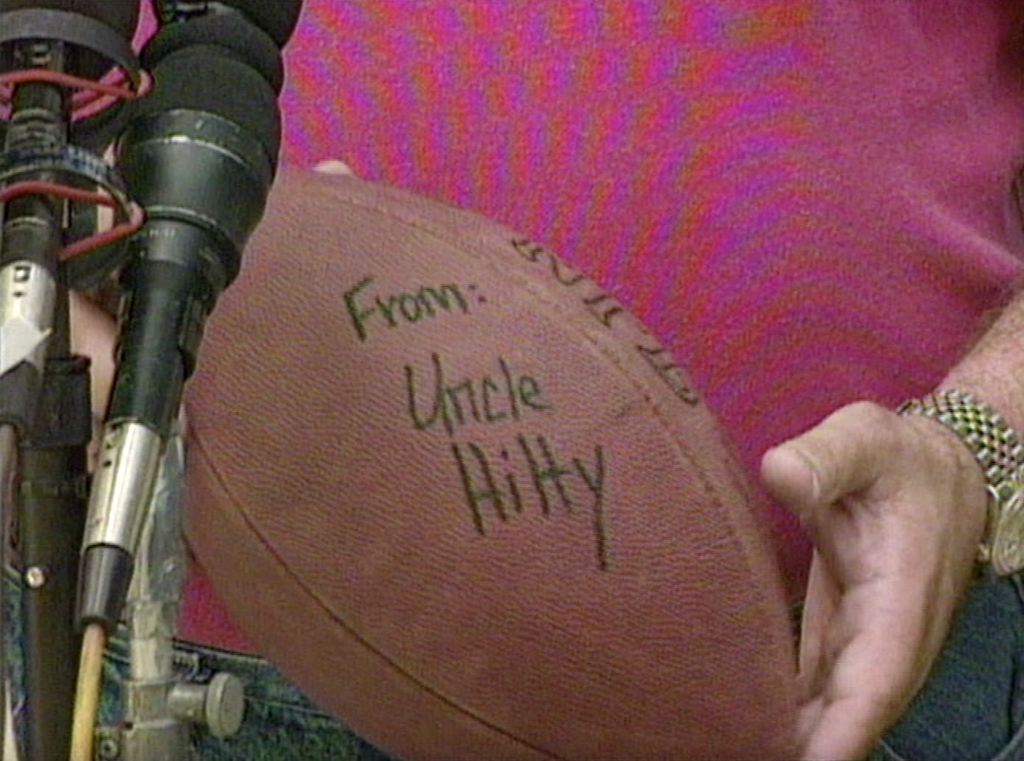

On the morning of the execution, author Tannie Shannon visited with Hilton Crawford. Hilton’s family decided not to witness the execution, but his son Chris visited for about an hour.

“And as he walked away, I saw Crawford kind-of turned around and he had tears just rolling down his cheeks,” said Tannie. “That was a very touching scene.”

Also there on that day was Hilton’s spiritual advisor, Rebecca.

“He really became religious after being on death row,” said Tannie Shannon.

Hilton had become a Franciscan monk, taking vows of poverty, chastity and obedience to God. Then again, a pledge to give up material wealth, love, and freedom isn’t much of a sacrifice for a death row inmate.

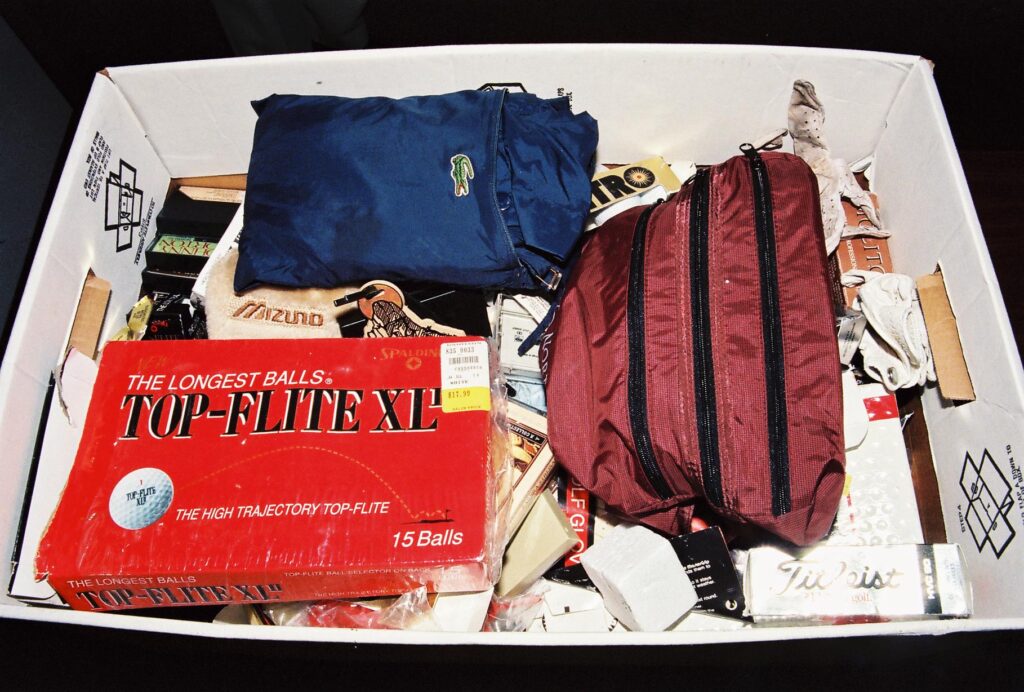

And when Hilton had opportunities for indulgence he didn’t seem to show much restraint.

“He said he had turned his life over to the Lord, but it looks like he turned his life over to his stomach,” said FBI agent Donnie Miller.

For his final meal, Hilton requested: twelve beef ribs, three enchiladas, chicken fried steak with cream gravy, a crispy bacon sandwich, ketchup, a loaf of bread, cobbler, three Cokes, three root beer, French fries, and onion rings.

“It was a gluttonous nirvana. I can’t imagine engorging yourself like that, tumescently, prior to execution, if you’ve really turned yourself over to the Lord. I don’t buy it all,” said Miller. “I don’t buy the R. L. Remington thing at all either.”

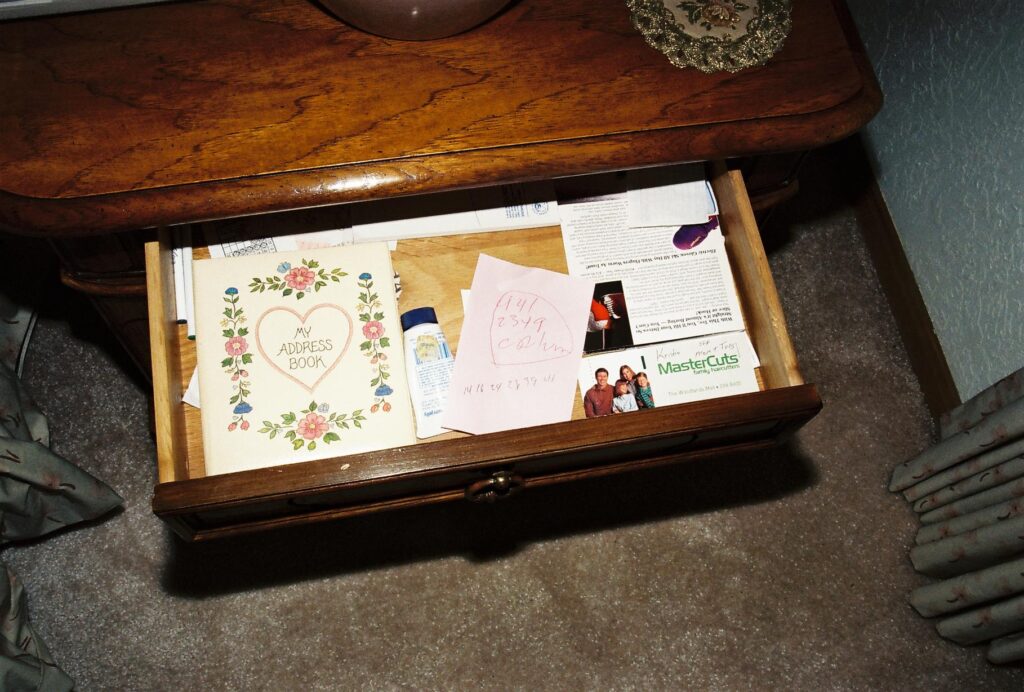

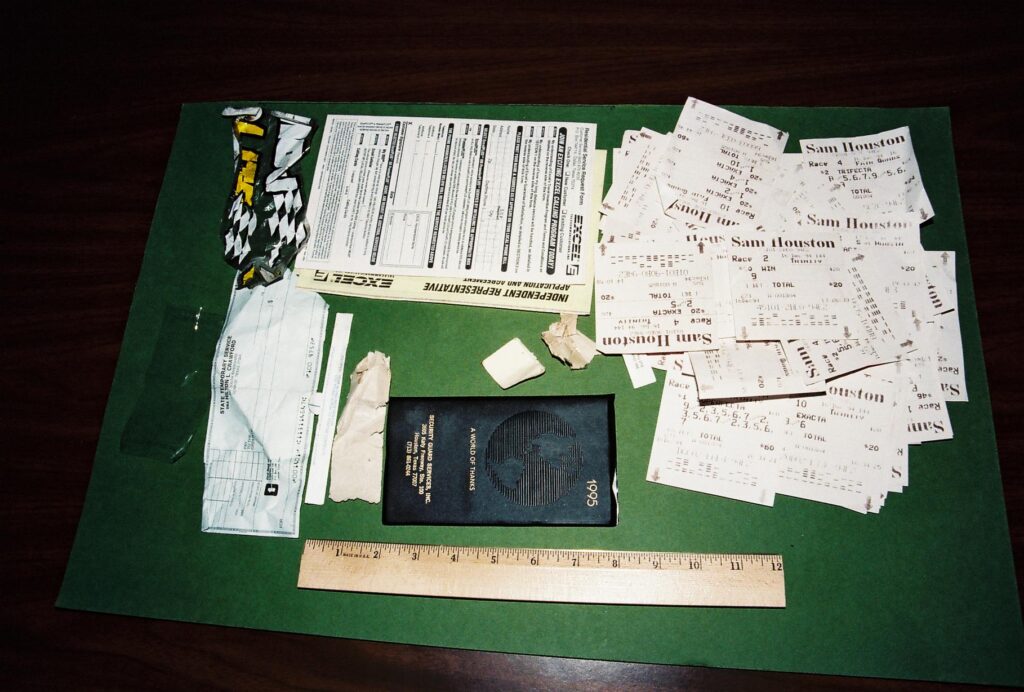

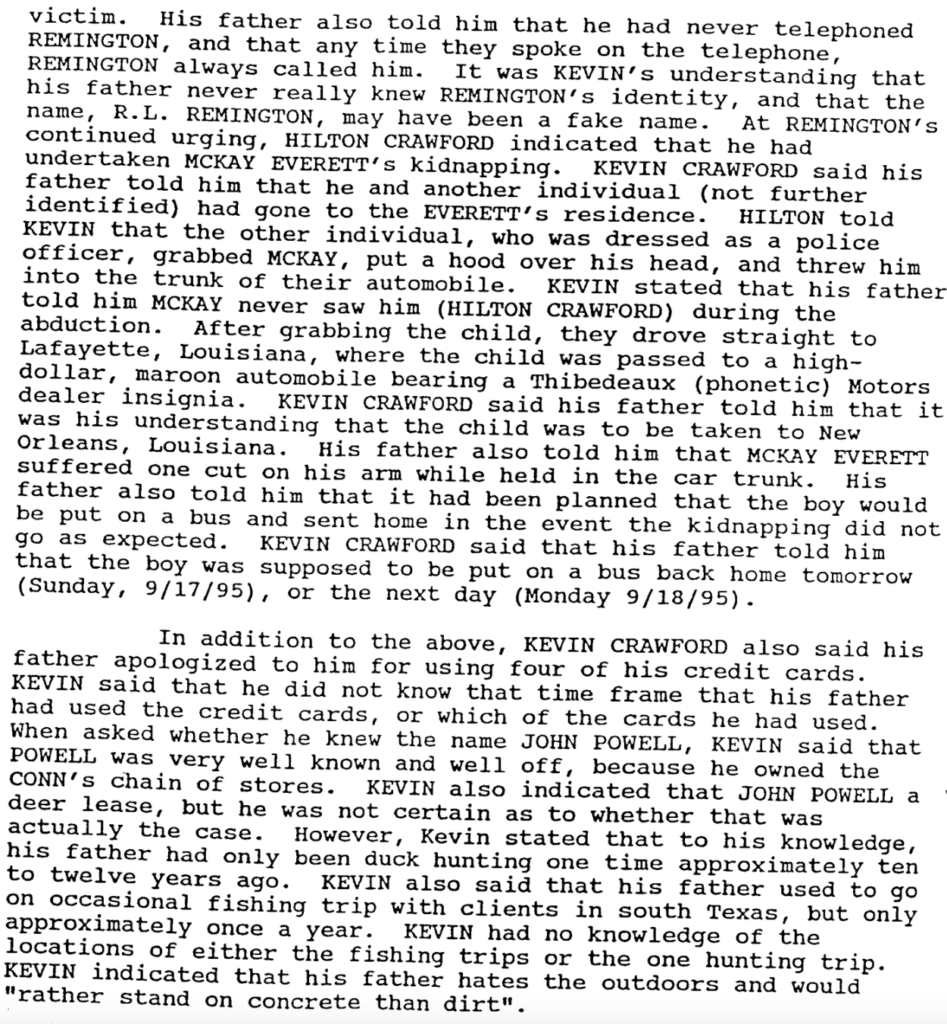

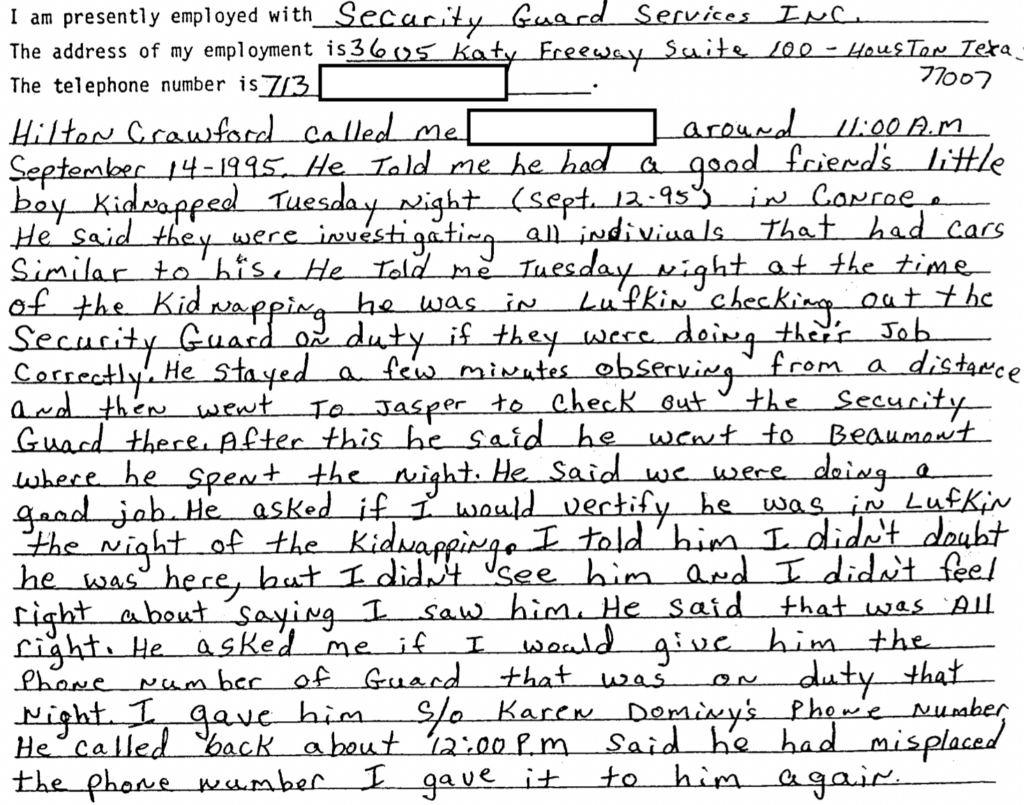

To his dying day, Hilton maintained that he hadn’t killed McKay Everett and that the real killer R. L. Remington was still out there somewhere. Hilton also continued to deny that gambling had been the source of his debt and problems, in fact, he’d continued gambling while in prison.

Author Tannie Shannon said that Hilton asked his spiritual advisor about it on his final day:

“He said, ‘Tell the truth – is gambling really a sin?’ And she said, ‘Hilton, you know, gambling is a sin.’ And he just kind-of looks down like this and shakes his head, he said, ‘I guess I’m going to be in line longer than I thought.’ On the day of his death. Can you imagine that?”

The Death Chamber

AP reporter Mike Graczyk has covered all of Texas’s executions since 1982 except one, and he’s personally witnessed over 400, giving him the dubious distinction of seeing the most executions in the United States — probably the whole world.

“The only other option, I guess, would be if someone I know that in the Middle East or in China,” said Graczyk. “They do them in mass, 20-30 at a time.”

Gracyzk earned that distinction because he got stationed in Huntsville in 1983 right after Texas re-started doing executions after an 18-year moratorium.

“The Supreme Court then in the mid-60s, put a moratorium on capital punishment in the whole country. And that moratorium lasted for about a decade until the mid-70s,” said Gracyzk.

In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled that capital punishment could resume, as long as it wasn’t used arbitrarily or capriciously. States needed to show that there were aggravating circumstances making the crimes particularly heinous and give perpetrators a chance to explain mitigating circumstances as well.

After that ruling, Texas revised its capital punishment laws and performed the world’s first execution by lethal injection on December 7th, 1982.

Over time, the way Texas conducts the death penalty has changed slightly. Now, the room where executions take place is split into three chambers: the death chamber where the inmate is executed, and two separate viewing chambers — one for the inmates invited witnesses, the other for the victim’s family. Each has barred windows looking into the death chamber.

Up until 1996, only the inmate’s friends and family were allowed to attend the execution.

“It can get pretty uncomfortable in there,” said Graczyk, describing an incident right after an inmate was put to death, “The mom hit the floor, hallucinating, hyperventilating.”

“There was one instance where somebody put his foot through the wall. I mean, they’ve had to take people out of the of the room because it was getting out of control.”

When a victim’s family members were first allowed to attend, Grazcyk thought they’d be even more emotional, but said “Ninety-nine percent of the time they’re all stoic.”

That’s probably in part because victims’ family members are warned before the execution that any outburst or bad behavior could result in other victims’ families losing the privilege.

The Execution

Paulette received such a warning at 6 pm, as a prison security officer led Paulette into the victim’s family viewing room of the Death House. Already Hilton was lying in the death chamber, strapped to a gurney with an IV in his arm, and a microphone suspended over his head.

Paulette was struck by the strangeness of the room, and the whole situation.

“Teeny tiny, low, low, low ceilings, and the ugliest green you’ve ever seen,” said Paulette. “And there’s this thing like a hospital examining table — like in one of those Frankenstein movies. Big, big straps, big belt loops. And I was like, what? Do they think he’s gonna get up and run? It was almost like satire.”

“He was wearing something around his neck that had a small wooden cross,” said Graczyk. “My notes show that he turned and looked at Paulette. He made a joke as we walked in about how he should have eaten more of his meal that he had selected.”

“I guess he thought he was some great public speaker,” said Paulette. “He had something to say. Well you know, it’s a little late. It’s just a little too late.”

Hilton Crawford began his final statement:

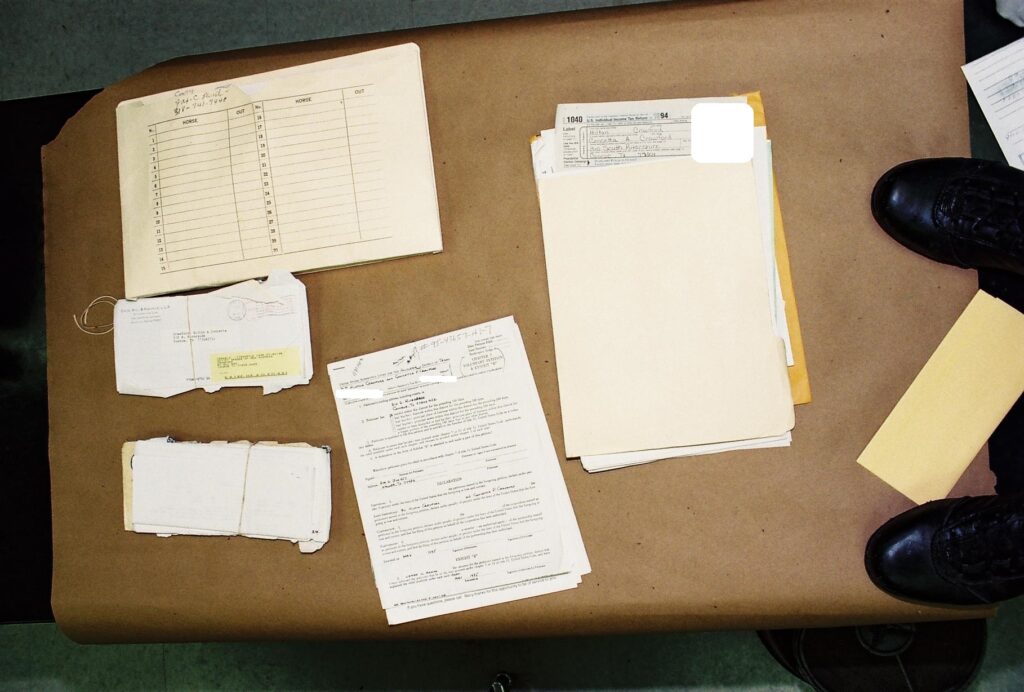

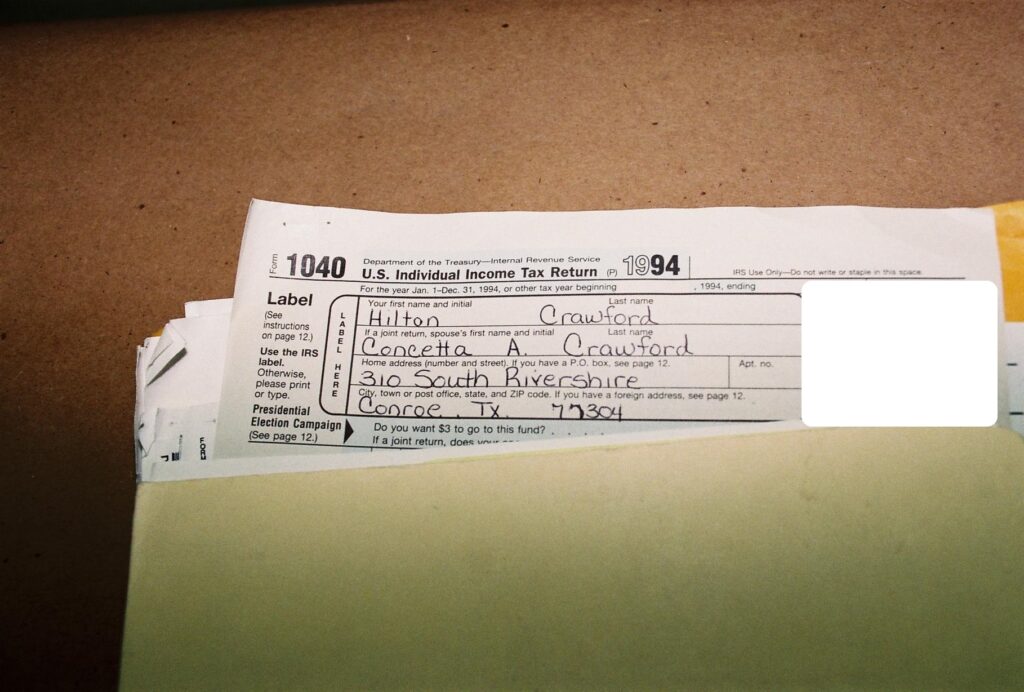

“First of all, I would like to ask Sister Teresa to send Connie a yellow rose. I want to thank the Lord, Jesus Christ, for the years I have spent on death row. They have been a blessing in my life. I have had the opportunity to serve Jesus Christ and I am thankful for the opportunity. I would like to thank Father Walsh for having become a Franciscan, and all the people all over the world who have become my friends. It has been a wonderful experience in my life. I would like to thank Chaplain Lopez, and my witnesses for giving me their support and love. I would like to thank the Nuns in England for their support. I want to tell my sons I love them; I have always loved them – they were my greatest gift from God. I want to tell my witnesses, Tannie, Rebecca, Al, Leo, and Dr. Blackwell that I love all of you and I am thankful for your support. I want to ask Paulette for forgiveness from your heart. One day, I hope you will. It is a tragedy for my family and your family. I am sorry. My special angel, I love you. And I love you, Connie. May God pass me over to the Kindom’s shore softly and gently. I am ready.”

“Once the final statement has been made by the inmates, then the drug is turned on,” said Grazcyk.

“You just stand there and watch,” said Paulette. “You know, his whole skin tone went through this series of levels of Lilac, purple, bluish, grayish until he was dead. And then I was like, That’s it?”

“Yeah, it’s very quick. They essentially go to sleep. They may cough or gasp a couple of times,” said Graczyk. “We’ve heard out we’ve heard comments, ‘Oh I can feel it. It’s cold, it’s hot. It burns, it smells, it tastes funny,’ … But, you know, thirty seconds later, they’re either snoring quietly … or there’s obviously no movement and they are either unconscious or they’re dead.”

The whole situation bothered Paulette. She thought Hilton Crawford had gotten off too easy: a final meal, a final statement, an anesthetic putting Crawford to sleep before he died — McKay had gotten none of those things.

And, in fact, in 2011 Texas stopped letting death-row inmates choose their final meal.

To hear more about Paulette’s reaction to Hilton’s execution and how Paulette moved forward and found new meaning and purpose in her life, listen to Ransom Episode 9 – Endings:

Ransom: Position of Trust is a nine-part true crime podcast from KSL Podcasts.

Follow the Ransom Podcast for free on your favorite podcast app. New episodes are released every Wednesday, with bonus episodes available on Fridays.